This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Read This Month: Abide" At Vouched Books on 03 March 2014.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

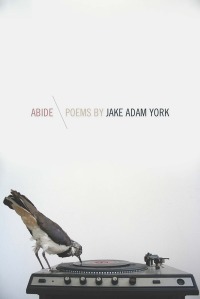

After recently receiving a copy of his posthumously released Abide (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014) in the mail, I was thankful for the opportunity to read new work by him; but that thankfulness was tempered by the sadness of knowing that he is no longer with us.

Abide serves to reinforce these conflicted feelings. On the one hand, the poems demonstrate York’s deft musicality, attention to craft, and adherence to an ethical imperative that originates in the historicity and spirit of the Civil Rights movement. On the other hand, the elegies therein resonant with sadly, prophetic echoes that often times seem to prefigure his own passing.

The poem “Mayflower,” for instance, is an elegy composed for John Earl Reese, who the poem’s dedication mentions was a “sixteen-year-old, shot by Klansmen through the window of a café” on “October 22, 1955.” The opening lines read:

As the poem proceeds, the speaker eventually levels an awful truth:

And one can only assume that York had much more to say. In the book’s concluding “Foreword to a Subsequent Reading,” Jake writes that his project of creating poetic monuments to the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement was, indeed:

To this end, York understood the necessary connection between memory and naming bound within breath: “We visit memory sites…but if memory lives on there, it isn’t memory anymore. Memory lives in the breath we breathe, in the air we make together” (80). We should, then, take this to declaration of breath to heart in order to keep both the memory of Civil Rights’ martyrs and York alive.

To do so, though, requires more than a visit to the physical site of a memorial or purchasing a book artifact. Rather, we must sing the names of the deceased through the silences. We must voice the names and recite aloud the poems, such that we begin “reaching / for the sound of some beyond” in order to create a “vibration” (8) that awakens the spirits and brings them to life through the audible word. Doing so will, in the end, reactivate the “Last breaths of the disappeared” (36) at and in the site of the poem. Or, as Jake himself wrote:

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.After recently receiving a copy of his posthumously released Abide (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014) in the mail, I was thankful for the opportunity to read new work by him; but that thankfulness was tempered by the sadness of knowing that he is no longer with us.

Abide serves to reinforce these conflicted feelings. On the one hand, the poems demonstrate York’s deft musicality, attention to craft, and adherence to an ethical imperative that originates in the historicity and spirit of the Civil Rights movement. On the other hand, the elegies therein resonant with sadly, prophetic echoes that often times seem to prefigure his own passing.

The poem “Mayflower,” for instance, is an elegy composed for John Earl Reese, who the poem’s dedication mentions was a “sixteen-year-old, shot by Klansmen through the window of a café” on “October 22, 1955.” The opening lines read:

Before the bird’s songWhile, certainly, one can read the passage on the surface level as a lament for Reese’s passing, it is not difficult—at least for this reader—to read these lines as premonitory: “Before the bird’s song,” or the release of the poems in Abide, all we can “hear” from York is the “quiet” or “silence” following his death. Upon publication, the effects of his death become “part of the song,” at least to the extent that the poet’s absence can be keenly felt (or read) in all of these poems.

you hear its quiet

which becomes part of the song

and lives on after,

struck notes bright

in silence (17)

As the poem proceeds, the speaker eventually levels an awful truth:

and a young man’s voiceYes, in the poems of Abide we hear the “young man’s voice” singing for us once more; but inherent to this music is the realization that the collection will be followed by the “young’s man’s / silence” and “all // he [will] not say.”

becomes a young man’s

silence, all

he did not say (18)

And one can only assume that York had much more to say. In the book’s concluding “Foreword to a Subsequent Reading,” Jake writes that his project of creating poetic monuments to the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement was, indeed:

always too big for one book. It is more complicated than a simple serial form, like a trilogy. It is the work of a life, both countless and one; one cannot predict how long it will take, but it will take as long as it will take. Abide continues, advances, event as it contains, as it remains. (79)While the completion of his project might not have reached full fruition, the four books York released do serve to “elegize” at least some of the “men, women, and children who were martyred between 1954 and 1968 as part of the freedom to struggle” (79) in a beautiful and earnest manner. Such elegies, it would appear, stem from both explicit and implicit prohibitions against articulating and celebrating these victims. Or, as the poem “Letter to be Wrapped around a 12-Inch Disc” states:

We had so muchYork’s poems, specifically the elegies, seek to rupture the “silence” by stirring up and remembering those names that others wanted to be left behind and forgotten in the forward march of history.

behind us, the history

we were told we shouldn’t

name, stir up, remember,

so much silence

we needed to break (11)

To this end, York understood the necessary connection between memory and naming bound within breath: “We visit memory sites…but if memory lives on there, it isn’t memory anymore. Memory lives in the breath we breathe, in the air we make together” (80). We should, then, take this to declaration of breath to heart in order to keep both the memory of Civil Rights’ martyrs and York alive.

To do so, though, requires more than a visit to the physical site of a memorial or purchasing a book artifact. Rather, we must sing the names of the deceased through the silences. We must voice the names and recite aloud the poems, such that we begin “reaching / for the sound of some beyond” in order to create a “vibration” (8) that awakens the spirits and brings them to life through the audible word. Doing so will, in the end, reactivate the “Last breaths of the disappeared” (36) at and in the site of the poem. Or, as Jake himself wrote:

Maybe we keep sayingAnd, indeed, by reciting the poems of Abide aloud while reading, the reader shapes York's voice within their own voice, such that the poet's memory haunts the lungs of another, imbuing the breath and body with the spirit of the deceased.

their silences between our words,

the shape of their voices

in ours, in ours

the warmth that haunts

their absent lungs. (34)

No comments:

Post a Comment