A website featuring my mixed media panels has now gone live. It's URL is www.joshua-ware.com. If you're interested in the larger, visual work I've been creating over the course of the past year, please check out the site.

If you're interested in purchasing any of the pieces, you can find my contact information at that address.

02 March 2017

13 October 2016

Vouched Books Archived Articles

Between 28 March 2013 and 11 April 2014, I wrote articles for the now-defunct Vouched Books. (Although the website currently is live, it occasionally disappears.) In order to preserve the articles I wrote, head editor Laura Relyea allowed me to migrate my pieces to my personal site for archival purposes. Outside of some shorter, filler pieces, every post I wrote during my tenure for Vouched Books can be found in reverse-chronological order on this blog. In total, there are 72 articles reproduced on this site.

Larissa Szporluk Introduction

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Larissa Szporluk" at Vouched Books on 11 April 2014.

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

I first became aware of Larissa Szporluk's poetry in 2004, when one of my graduate school professors, the late-Jake Adam York, mentioned her as someone he considered to be one of the premier, contemporary poets writing at the time. Specifically, he directed me to her third, full-length collection of poetry, The Wind, Master Cherry, The Wind (Alice James Books, 2003).

While reading the book, I was struck by the ability of Szporluk’s poems to challenge not only the manner in which we use language, but their capacity to fundamentally alter the way in which we view the world; or, as she herself wrote in the poem “Death of Magellan”:

This semester, though, my students and I read her most recent book, Traffic with MacBeth (Tupelo Press, 2011), which, among other things, explores what happens when “violence takes over” (26) both the natural and human worlds. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the poem “Mouth Horror”:

The violence that permeates natural world, though, does not remain within its bounds; rather, it overflows into the human realm by way story and myth. For example, in the opening stanza of the poem “Baba Yaga”; the poem’s namesake, who is a sorceress from Slavic folklore, tells us that:

To this end, I think, the purpose of Traffic with MacBeth's violence is to provide us with a heightened awareness of the fragility of life; and, thus, instills within us a greater appreciation for our brevity.

Here's a video clip of Szporluk reading her poem "Flight of the Mice" from her first collection Dark Sky Question (Beacon Press, 1998):

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:I first became aware of Larissa Szporluk's poetry in 2004, when one of my graduate school professors, the late-Jake Adam York, mentioned her as someone he considered to be one of the premier, contemporary poets writing at the time. Specifically, he directed me to her third, full-length collection of poetry, The Wind, Master Cherry, The Wind (Alice James Books, 2003).

While reading the book, I was struck by the ability of Szporluk’s poems to challenge not only the manner in which we use language, but their capacity to fundamentally alter the way in which we view the world; or, as she herself wrote in the poem “Death of Magellan”:

Heaven was lostYes, just as Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe altered humanity’s spatial relationship to/of the world during the sixteenth century--literally changing our notion of what "up and down" meant--Szporluk’s poems changed the manner in which I conceived of both language and poetry at a time when I was primarily familiar with the canonical and anthologized poems taught in literature courses. More than a decade ago, then, her poems acted as a literary and poetic passage that was theretofore uncharted for me.

when up and down

lost meaning. (5)

This semester, though, my students and I read her most recent book, Traffic with MacBeth (Tupelo Press, 2011), which, among other things, explores what happens when “violence takes over” (26) both the natural and human worlds. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the poem “Mouth Horror”:

Five male cricketsThe poem presents the reader with the seemingly benign image of crickets chirping on a summer evening; but the moment quickly transforms it into a Darwinian struggle, wherein the “loudest” crickets “win,” such that their “chirp[s]” become “swords” that leave the “loser[s to] rot”:

sing and fight.

The loudest wins,

the softest dies (38)

into the sweet black goreSuch violence manifests itself again and again throughout Traffic's representations of the natural world, as seen in the wind that “leaves a deep pocket / of dusk in your scalp” (3), a ladybird “carcass / on a snow-white beach” (7), or the image of an “eye of the cat-torn mouse” (41).

of cricket joy

expressed to death

in one dumb glop (38)

The violence that permeates natural world, though, does not remain within its bounds; rather, it overflows into the human realm by way story and myth. For example, in the opening stanza of the poem “Baba Yaga”; the poem’s namesake, who is a sorceress from Slavic folklore, tells us that:

I cooked my little children in the sun.While, no doubt, this moment of infanticide demonstrates most evidently the violence inherent to the human world, there are also minor violences, often self-inflicted, that occur throughout the collection. In the poem “Accordion,” the speaker notes:

I threw grass on them and then they died.

I sit here and wonder what I’ve done. (47)

When the blood leaves my arm at night,Indeed, something as mundane as sleeping on one’s arm so as to cut-off circulation, thus inducing that “pins-and-needles” feeling, offers us a meditation on death that confers upon us the understanding that “being dead, is easy”—at least to the extent that its specter is ever-present and always near.

my arm is independent.

I hold it up, my own dead arm,

and flap it at the sleepers

in adjoining rooms around me.

Beating time, like being dead, is easy. (41)

To this end, I think, the purpose of Traffic with MacBeth's violence is to provide us with a heightened awareness of the fragility of life; and, thus, instills within us a greater appreciation for our brevity.

Here's a video clip of Szporluk reading her poem "Flight of the Mice" from her first collection Dark Sky Question (Beacon Press, 1998):

The Art of Ian Huebert

This article firt appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Read This Week: Ian Huebert" at Vouched Books on 04 April 2014.

If you don't recognize the name Ian Huebert, you probably have, at least, seen his work. Most recently, Huebert designed the cover for Matthew Zapruder's newest collection of poems Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014). He also created the cover art for Dan Chelott's X (McSweeney's, 2013), Jeff Alessandrelli's Don't Let Me Forget to Feed the Sharks (Poor Claudia, 2012), and is the primary cover artist for the chapbooks released by Dikembe Press.

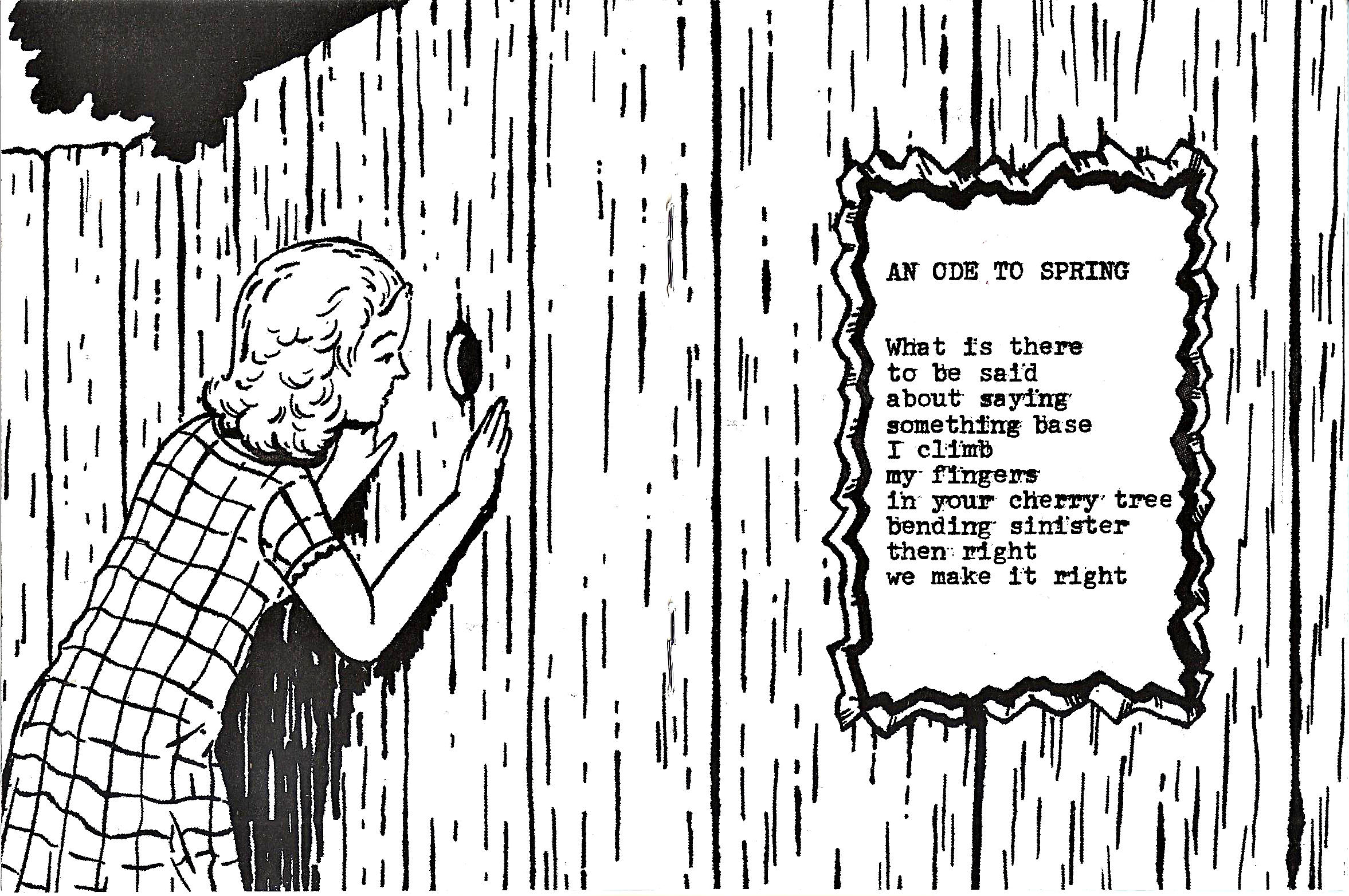

In addition to designing covers for collection of contemporary poetry, though, Huebert also is an accomplished cartoonist and minimalist poet. Over the course of the past year or two, he has self-published a limited-run chapbook series of his drawings and poetry, titled Comb. Take a look at the below excerpt from issue one (click for large view):

One of my favorite aspects of the above image is how the text of the poem appears to both rupture the aesthetic surface of the cartoon, while simultaneously integrating itself into the image rather seamlessly. At least as a visual text, its ability to look both coherent and fractured is something that pleases me. (My critical vocabulary for visual art is limited, so my apologies for any idiomatic lack.)

As far as the poem itself, I enjoy how Huebert transforms a rather benign, childhood activity, such as climbing a "cherry tree," into a "base," sexual experience. Likewise, the wordplay via repetition and difference (i.e. "said" and "saying) and homonyms (i.e. "right") adds another dimension of linguistic depth within the rather small space of ten lines.

Moreover, the sexual transformation that occurs in the poem alters our interpretation of the image; a child peeking through a hole in a fence becomes a moment of voyeuristic, sexual gratification instead of an innocent moment of childhood "spying."

If you'd like to purchase a copy of issues one and two of Comb, or any of the other various woodcuts and prints Huebert has made, check out both his website or his tumblr account. You can also find a handful of Huebert's poems in this year's Lovebook by SP CE.

If you don't recognize the name Ian Huebert, you probably have, at least, seen his work. Most recently, Huebert designed the cover for Matthew Zapruder's newest collection of poems Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014). He also created the cover art for Dan Chelott's X (McSweeney's, 2013), Jeff Alessandrelli's Don't Let Me Forget to Feed the Sharks (Poor Claudia, 2012), and is the primary cover artist for the chapbooks released by Dikembe Press.

In addition to designing covers for collection of contemporary poetry, though, Huebert also is an accomplished cartoonist and minimalist poet. Over the course of the past year or two, he has self-published a limited-run chapbook series of his drawings and poetry, titled Comb. Take a look at the below excerpt from issue one (click for large view):

One of my favorite aspects of the above image is how the text of the poem appears to both rupture the aesthetic surface of the cartoon, while simultaneously integrating itself into the image rather seamlessly. At least as a visual text, its ability to look both coherent and fractured is something that pleases me. (My critical vocabulary for visual art is limited, so my apologies for any idiomatic lack.)

As far as the poem itself, I enjoy how Huebert transforms a rather benign, childhood activity, such as climbing a "cherry tree," into a "base," sexual experience. Likewise, the wordplay via repetition and difference (i.e. "said" and "saying) and homonyms (i.e. "right") adds another dimension of linguistic depth within the rather small space of ten lines.

Moreover, the sexual transformation that occurs in the poem alters our interpretation of the image; a child peeking through a hole in a fence becomes a moment of voyeuristic, sexual gratification instead of an innocent moment of childhood "spying."

If you'd like to purchase a copy of issues one and two of Comb, or any of the other various woodcuts and prints Huebert has made, check out both his website or his tumblr account. You can also find a handful of Huebert's poems in this year's Lovebook by SP CE.

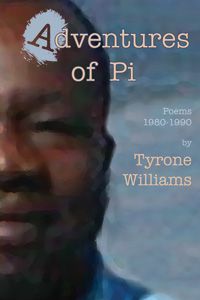

Tyrone Williams Introduction

This article first ppeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Tyrone Williams" at Vouched Books on 28 March 2014.

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

In late-2002, I began actively exploring the world of contemporary poetry. As a way to discover the names of poets, presses, and different aesthetics that interested me, I started reading pretty much any literary journal I could get my hands on. After a few months of scouring the small press and magazine section at Tattered Cover in downtown Denver, I found myself gravitating toward journals such as The Canary, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, Open City, and Verse.

In one of these magazines, the Fall/Winter 2003 issue of Fence, an article by Rodeny Phillips appeared that was titled “Exotic flowers, decayed gods, and the fall of paganism: The 2003 Poets House Poetry Showcase, an exhibit of poetry books published in 2002.” In addition to providing a comprehensive overview of the showcase, several sidebars located in the article’s margins offered “Best Of” lists: “Best Books of Experimental Poetry” and “Best Debut Collections,” for example. While each list contained a series of names and titles with which I was unfamiliar—but, subsequently, over the years would become intimately familiar—one name caught my attention due to the fact that it found its way onto no less than three of these lists (if my memory serves me correctly): Tyrone Williams and his first book c.c., published by Krupskaya Press.

Given that the Phillips' article championed this poet and collection to such a high degree, I went online and ordered a copy. When the book finally arrived and I read through it, I was confronted with a style of poetry that was theretofore unknown to me. The writing in Williams’ first book employed radical notions of form, citation, appropriation, and marginalia, all the while remaining socially, politically, and culturally engaged. This, indeed, was not the type of poetry I had previously encountered (even with exposure to the High Modernists); no, this was something more daring, complex, and exciting. The poems of c.c., such as “Cold Calls,” “I am not Proud to be Black,” and “TAG” were avant-tour de forces that acted as catalysts for my own interest, involvement, and dedication to poetry over the course of the next twelve years.

In 2008, Omnidawn Publishing released Williams’ second book of poetry On Spec, which I would later use for my comprehensive exams as I pursued my doctorate. In a citation of his book that I wrote in 2010, I argued that the collection “explores the confluence of post-Language poetry and African-American poetic tradition” by entwining “diverse aesthetic and ideological lineages” through the use of “different idioms and whose contents are often thought to be at odds with one another.” Moreover, I noted the book’s “conflation of genres,” wherein the poems sought to “question the relationship between theory and poetry,” as well as drama; in doing so, Williams created a “transitional and often nebulous zone.” These “boundary-defying techniques” were further highlighted in his “use of check-boxes, errata and footnotes…mathematical equations, cross-outs, quotation, and liberal use of white space.”

Most recently, his 2011 collection Howell (Atelos Press), which is a reference to Howell, Michigan and conceived in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, is an epic “writing through” of history that extends to nearly 400 pages in length.

For our course this semester, though, we read Williams’ Adventures of Pi: Poems 1980-1990. The collection takes a backward glance at the poet’s work, thus functioning as an interesting prequel in the development of a contemporary, poetic innovator. And although it does serve to flesh out his career trajectory, Adventures of Pi also offers readers engaging moments wherein the poet confronts the racial fissures in then-contemporary America in a straightforward but aesthetically compelling manner. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from his poem “White Noise (Fighting to Wake Up)”:

Similarly, racial and cultural issues are addressed and challenged throughout the collection in poems such as “A Black Man Who Wants to be a White Woman” and “How Do I Cross Out the X Malcom.” Within these poems, Williams creates linguistic spaces wherein he’s “Scribabbling” his words into an “estranged language” (34) of neologism and wordplay in order to write a:

Here's a video clip of Williams reading his poem "Mayhem" from The Hero Project of the Century:

The final event of the semester for the Poets of Ohio reading series will take place on Thursday, 10 April when the poet Larissa Szporluk will visit Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH.

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:In late-2002, I began actively exploring the world of contemporary poetry. As a way to discover the names of poets, presses, and different aesthetics that interested me, I started reading pretty much any literary journal I could get my hands on. After a few months of scouring the small press and magazine section at Tattered Cover in downtown Denver, I found myself gravitating toward journals such as The Canary, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, Open City, and Verse.

In one of these magazines, the Fall/Winter 2003 issue of Fence, an article by Rodeny Phillips appeared that was titled “Exotic flowers, decayed gods, and the fall of paganism: The 2003 Poets House Poetry Showcase, an exhibit of poetry books published in 2002.” In addition to providing a comprehensive overview of the showcase, several sidebars located in the article’s margins offered “Best Of” lists: “Best Books of Experimental Poetry” and “Best Debut Collections,” for example. While each list contained a series of names and titles with which I was unfamiliar—but, subsequently, over the years would become intimately familiar—one name caught my attention due to the fact that it found its way onto no less than three of these lists (if my memory serves me correctly): Tyrone Williams and his first book c.c., published by Krupskaya Press.

Given that the Phillips' article championed this poet and collection to such a high degree, I went online and ordered a copy. When the book finally arrived and I read through it, I was confronted with a style of poetry that was theretofore unknown to me. The writing in Williams’ first book employed radical notions of form, citation, appropriation, and marginalia, all the while remaining socially, politically, and culturally engaged. This, indeed, was not the type of poetry I had previously encountered (even with exposure to the High Modernists); no, this was something more daring, complex, and exciting. The poems of c.c., such as “Cold Calls,” “I am not Proud to be Black,” and “TAG” were avant-tour de forces that acted as catalysts for my own interest, involvement, and dedication to poetry over the course of the next twelve years.

In 2008, Omnidawn Publishing released Williams’ second book of poetry On Spec, which I would later use for my comprehensive exams as I pursued my doctorate. In a citation of his book that I wrote in 2010, I argued that the collection “explores the confluence of post-Language poetry and African-American poetic tradition” by entwining “diverse aesthetic and ideological lineages” through the use of “different idioms and whose contents are often thought to be at odds with one another.” Moreover, I noted the book’s “conflation of genres,” wherein the poems sought to “question the relationship between theory and poetry,” as well as drama; in doing so, Williams created a “transitional and often nebulous zone.” These “boundary-defying techniques” were further highlighted in his “use of check-boxes, errata and footnotes…mathematical equations, cross-outs, quotation, and liberal use of white space.”

Most recently, his 2011 collection Howell (Atelos Press), which is a reference to Howell, Michigan and conceived in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, is an epic “writing through” of history that extends to nearly 400 pages in length.

For our course this semester, though, we read Williams’ Adventures of Pi: Poems 1980-1990. The collection takes a backward glance at the poet’s work, thus functioning as an interesting prequel in the development of a contemporary, poetic innovator. And although it does serve to flesh out his career trajectory, Adventures of Pi also offers readers engaging moments wherein the poet confronts the racial fissures in then-contemporary America in a straightforward but aesthetically compelling manner. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from his poem “White Noise (Fighting to Wake Up)”:

of a body dreaming two dreams,The notion that two dreams and two Americas exist within the speaker echoes, at least to me, the concept of double-consciousness as proposed by W.E.B. DuBois in The Souls of Black Folk, in which he famously wrote:

only one of which is called

a black man in America,

the other, America

itself (18)

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.Furthermore, the form of Williams’ poem suggests an intensification of this “two-ness” through a strategic use of a stanza break between the two instances of “America” within the single, syntactical unit. In this sense, the poem fuses form and content in order to heighten its underlying conceptual framework.

Similarly, racial and cultural issues are addressed and challenged throughout the collection in poems such as “A Black Man Who Wants to be a White Woman” and “How Do I Cross Out the X Malcom.” Within these poems, Williams creates linguistic spaces wherein he’s “Scribabbling” his words into an “estranged language” (34) of neologism and wordplay in order to write a:

story we make up about the other storiesYes, stories made up of stories compound by other stories, all constructing an American narrative that resonates with the “Remarkable violence” inherent to the history of a country fraught with civil rights’ tensions and complex racial relations. But far from simply being a collection of didactic poems, Williams employs his heightened intellect, aesthetic sensibilities, and ear for the musical phrase in order to compose poems that address the political and social worlds while simultaneously providing aesthetic pleasures. In doing so, the poems challenge both our understanding of contemporary poetry and our concept of race in America today.

[Which] Itself is made up of other stories:

Thus the three dimensions of history—plus history,

Remarkable violence (34)

Here's a video clip of Williams reading his poem "Mayhem" from The Hero Project of the Century:

The final event of the semester for the Poets of Ohio reading series will take place on Thursday, 10 April when the poet Larissa Szporluk will visit Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)