Between 28 March 2013 and 11 April 2014, I wrote articles for the now-defunct Vouched Books. (Although the website currently is live, it occasionally disappears.) In order to preserve the articles I wrote, head editor Laura Relyea allowed me to migrate my pieces to my personal site for archival purposes. Outside of some shorter, filler pieces, every post I wrote during my tenure for Vouched Books can be found in reverse-chronological order on this blog. In total, there are 72 articles reproduced on this site.

13 October 2016

Larissa Szporluk Introduction

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Larissa Szporluk" at Vouched Books on 11 April 2014.

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

I first became aware of Larissa Szporluk's poetry in 2004, when one of my graduate school professors, the late-Jake Adam York, mentioned her as someone he considered to be one of the premier, contemporary poets writing at the time. Specifically, he directed me to her third, full-length collection of poetry, The Wind, Master Cherry, The Wind (Alice James Books, 2003).

While reading the book, I was struck by the ability of Szporluk’s poems to challenge not only the manner in which we use language, but their capacity to fundamentally alter the way in which we view the world; or, as she herself wrote in the poem “Death of Magellan”:

This semester, though, my students and I read her most recent book, Traffic with MacBeth (Tupelo Press, 2011), which, among other things, explores what happens when “violence takes over” (26) both the natural and human worlds. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the poem “Mouth Horror”:

The violence that permeates natural world, though, does not remain within its bounds; rather, it overflows into the human realm by way story and myth. For example, in the opening stanza of the poem “Baba Yaga”; the poem’s namesake, who is a sorceress from Slavic folklore, tells us that:

To this end, I think, the purpose of Traffic with MacBeth's violence is to provide us with a heightened awareness of the fragility of life; and, thus, instills within us a greater appreciation for our brevity.

Here's a video clip of Szporluk reading her poem "Flight of the Mice" from her first collection Dark Sky Question (Beacon Press, 1998):

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:

For final event of this season's Poets of Ohio reading series, Larissa Szporluk visited Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH to read and discuss her poetry. Below is an excerpt from my introduction to the event, as well as a video clip of her reading one of her poems:I first became aware of Larissa Szporluk's poetry in 2004, when one of my graduate school professors, the late-Jake Adam York, mentioned her as someone he considered to be one of the premier, contemporary poets writing at the time. Specifically, he directed me to her third, full-length collection of poetry, The Wind, Master Cherry, The Wind (Alice James Books, 2003).

While reading the book, I was struck by the ability of Szporluk’s poems to challenge not only the manner in which we use language, but their capacity to fundamentally alter the way in which we view the world; or, as she herself wrote in the poem “Death of Magellan”:

Heaven was lostYes, just as Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe altered humanity’s spatial relationship to/of the world during the sixteenth century--literally changing our notion of what "up and down" meant--Szporluk’s poems changed the manner in which I conceived of both language and poetry at a time when I was primarily familiar with the canonical and anthologized poems taught in literature courses. More than a decade ago, then, her poems acted as a literary and poetic passage that was theretofore uncharted for me.

when up and down

lost meaning. (5)

This semester, though, my students and I read her most recent book, Traffic with MacBeth (Tupelo Press, 2011), which, among other things, explores what happens when “violence takes over” (26) both the natural and human worlds. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the poem “Mouth Horror”:

Five male cricketsThe poem presents the reader with the seemingly benign image of crickets chirping on a summer evening; but the moment quickly transforms it into a Darwinian struggle, wherein the “loudest” crickets “win,” such that their “chirp[s]” become “swords” that leave the “loser[s to] rot”:

sing and fight.

The loudest wins,

the softest dies (38)

into the sweet black goreSuch violence manifests itself again and again throughout Traffic's representations of the natural world, as seen in the wind that “leaves a deep pocket / of dusk in your scalp” (3), a ladybird “carcass / on a snow-white beach” (7), or the image of an “eye of the cat-torn mouse” (41).

of cricket joy

expressed to death

in one dumb glop (38)

The violence that permeates natural world, though, does not remain within its bounds; rather, it overflows into the human realm by way story and myth. For example, in the opening stanza of the poem “Baba Yaga”; the poem’s namesake, who is a sorceress from Slavic folklore, tells us that:

I cooked my little children in the sun.While, no doubt, this moment of infanticide demonstrates most evidently the violence inherent to the human world, there are also minor violences, often self-inflicted, that occur throughout the collection. In the poem “Accordion,” the speaker notes:

I threw grass on them and then they died.

I sit here and wonder what I’ve done. (47)

When the blood leaves my arm at night,Indeed, something as mundane as sleeping on one’s arm so as to cut-off circulation, thus inducing that “pins-and-needles” feeling, offers us a meditation on death that confers upon us the understanding that “being dead, is easy”—at least to the extent that its specter is ever-present and always near.

my arm is independent.

I hold it up, my own dead arm,

and flap it at the sleepers

in adjoining rooms around me.

Beating time, like being dead, is easy. (41)

To this end, I think, the purpose of Traffic with MacBeth's violence is to provide us with a heightened awareness of the fragility of life; and, thus, instills within us a greater appreciation for our brevity.

Here's a video clip of Szporluk reading her poem "Flight of the Mice" from her first collection Dark Sky Question (Beacon Press, 1998):

The Art of Ian Huebert

This article firt appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Read This Week: Ian Huebert" at Vouched Books on 04 April 2014.

If you don't recognize the name Ian Huebert, you probably have, at least, seen his work. Most recently, Huebert designed the cover for Matthew Zapruder's newest collection of poems Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014). He also created the cover art for Dan Chelott's X (McSweeney's, 2013), Jeff Alessandrelli's Don't Let Me Forget to Feed the Sharks (Poor Claudia, 2012), and is the primary cover artist for the chapbooks released by Dikembe Press.

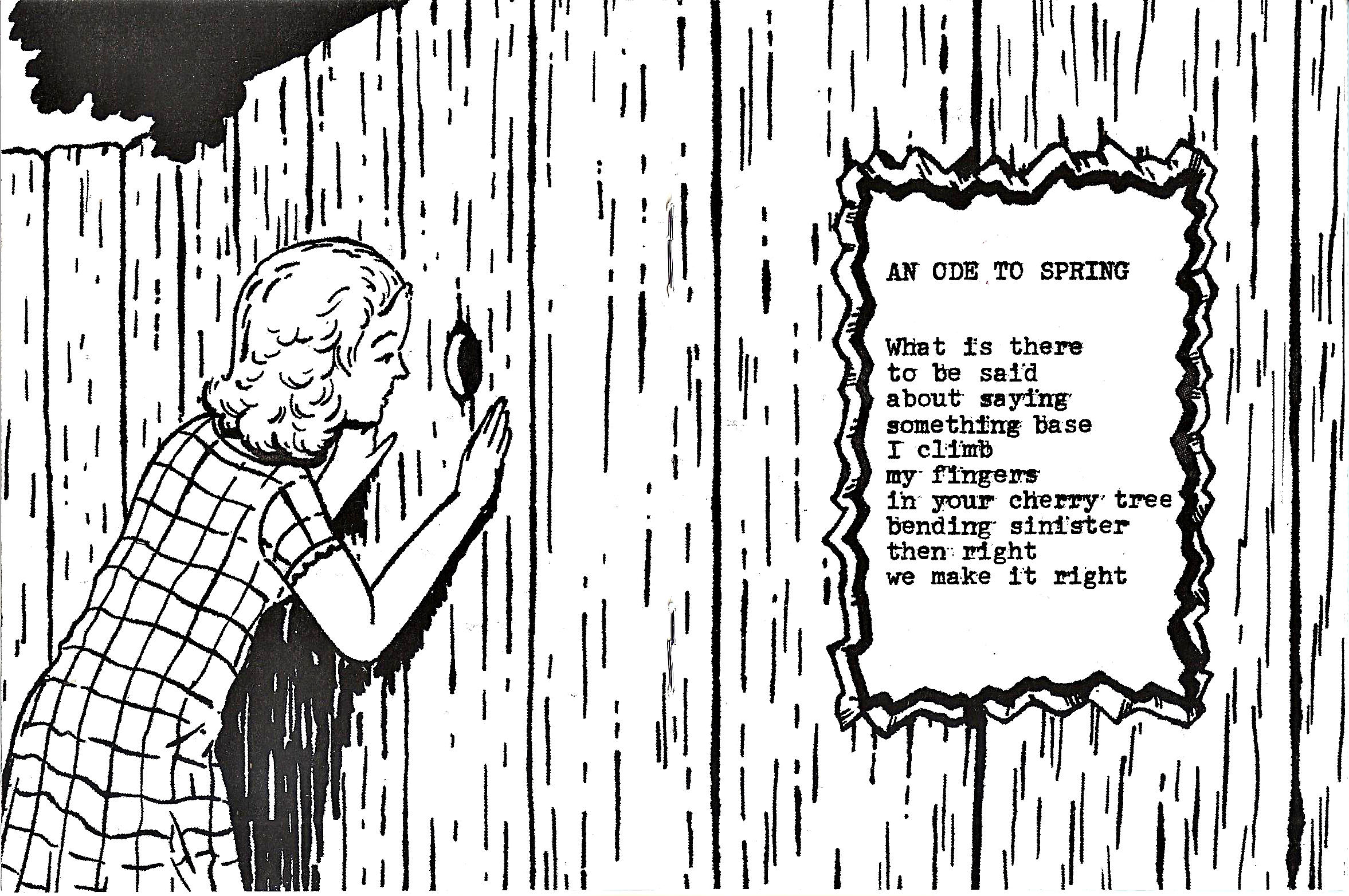

In addition to designing covers for collection of contemporary poetry, though, Huebert also is an accomplished cartoonist and minimalist poet. Over the course of the past year or two, he has self-published a limited-run chapbook series of his drawings and poetry, titled Comb. Take a look at the below excerpt from issue one (click for large view):

One of my favorite aspects of the above image is how the text of the poem appears to both rupture the aesthetic surface of the cartoon, while simultaneously integrating itself into the image rather seamlessly. At least as a visual text, its ability to look both coherent and fractured is something that pleases me. (My critical vocabulary for visual art is limited, so my apologies for any idiomatic lack.)

As far as the poem itself, I enjoy how Huebert transforms a rather benign, childhood activity, such as climbing a "cherry tree," into a "base," sexual experience. Likewise, the wordplay via repetition and difference (i.e. "said" and "saying) and homonyms (i.e. "right") adds another dimension of linguistic depth within the rather small space of ten lines.

Moreover, the sexual transformation that occurs in the poem alters our interpretation of the image; a child peeking through a hole in a fence becomes a moment of voyeuristic, sexual gratification instead of an innocent moment of childhood "spying."

If you'd like to purchase a copy of issues one and two of Comb, or any of the other various woodcuts and prints Huebert has made, check out both his website or his tumblr account. You can also find a handful of Huebert's poems in this year's Lovebook by SP CE.

If you don't recognize the name Ian Huebert, you probably have, at least, seen his work. Most recently, Huebert designed the cover for Matthew Zapruder's newest collection of poems Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014). He also created the cover art for Dan Chelott's X (McSweeney's, 2013), Jeff Alessandrelli's Don't Let Me Forget to Feed the Sharks (Poor Claudia, 2012), and is the primary cover artist for the chapbooks released by Dikembe Press.

In addition to designing covers for collection of contemporary poetry, though, Huebert also is an accomplished cartoonist and minimalist poet. Over the course of the past year or two, he has self-published a limited-run chapbook series of his drawings and poetry, titled Comb. Take a look at the below excerpt from issue one (click for large view):

One of my favorite aspects of the above image is how the text of the poem appears to both rupture the aesthetic surface of the cartoon, while simultaneously integrating itself into the image rather seamlessly. At least as a visual text, its ability to look both coherent and fractured is something that pleases me. (My critical vocabulary for visual art is limited, so my apologies for any idiomatic lack.)

As far as the poem itself, I enjoy how Huebert transforms a rather benign, childhood activity, such as climbing a "cherry tree," into a "base," sexual experience. Likewise, the wordplay via repetition and difference (i.e. "said" and "saying) and homonyms (i.e. "right") adds another dimension of linguistic depth within the rather small space of ten lines.

Moreover, the sexual transformation that occurs in the poem alters our interpretation of the image; a child peeking through a hole in a fence becomes a moment of voyeuristic, sexual gratification instead of an innocent moment of childhood "spying."

If you'd like to purchase a copy of issues one and two of Comb, or any of the other various woodcuts and prints Huebert has made, check out both his website or his tumblr account. You can also find a handful of Huebert's poems in this year's Lovebook by SP CE.

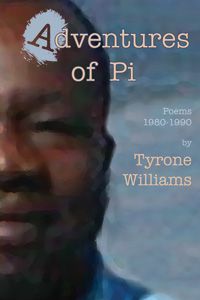

Tyrone Williams Introduction

This article first ppeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Tyrone Williams" at Vouched Books on 28 March 2014.

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

In late-2002, I began actively exploring the world of contemporary poetry. As a way to discover the names of poets, presses, and different aesthetics that interested me, I started reading pretty much any literary journal I could get my hands on. After a few months of scouring the small press and magazine section at Tattered Cover in downtown Denver, I found myself gravitating toward journals such as The Canary, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, Open City, and Verse.

In one of these magazines, the Fall/Winter 2003 issue of Fence, an article by Rodeny Phillips appeared that was titled “Exotic flowers, decayed gods, and the fall of paganism: The 2003 Poets House Poetry Showcase, an exhibit of poetry books published in 2002.” In addition to providing a comprehensive overview of the showcase, several sidebars located in the article’s margins offered “Best Of” lists: “Best Books of Experimental Poetry” and “Best Debut Collections,” for example. While each list contained a series of names and titles with which I was unfamiliar—but, subsequently, over the years would become intimately familiar—one name caught my attention due to the fact that it found its way onto no less than three of these lists (if my memory serves me correctly): Tyrone Williams and his first book c.c., published by Krupskaya Press.

Given that the Phillips' article championed this poet and collection to such a high degree, I went online and ordered a copy. When the book finally arrived and I read through it, I was confronted with a style of poetry that was theretofore unknown to me. The writing in Williams’ first book employed radical notions of form, citation, appropriation, and marginalia, all the while remaining socially, politically, and culturally engaged. This, indeed, was not the type of poetry I had previously encountered (even with exposure to the High Modernists); no, this was something more daring, complex, and exciting. The poems of c.c., such as “Cold Calls,” “I am not Proud to be Black,” and “TAG” were avant-tour de forces that acted as catalysts for my own interest, involvement, and dedication to poetry over the course of the next twelve years.

In 2008, Omnidawn Publishing released Williams’ second book of poetry On Spec, which I would later use for my comprehensive exams as I pursued my doctorate. In a citation of his book that I wrote in 2010, I argued that the collection “explores the confluence of post-Language poetry and African-American poetic tradition” by entwining “diverse aesthetic and ideological lineages” through the use of “different idioms and whose contents are often thought to be at odds with one another.” Moreover, I noted the book’s “conflation of genres,” wherein the poems sought to “question the relationship between theory and poetry,” as well as drama; in doing so, Williams created a “transitional and often nebulous zone.” These “boundary-defying techniques” were further highlighted in his “use of check-boxes, errata and footnotes…mathematical equations, cross-outs, quotation, and liberal use of white space.”

Most recently, his 2011 collection Howell (Atelos Press), which is a reference to Howell, Michigan and conceived in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, is an epic “writing through” of history that extends to nearly 400 pages in length.

For our course this semester, though, we read Williams’ Adventures of Pi: Poems 1980-1990. The collection takes a backward glance at the poet’s work, thus functioning as an interesting prequel in the development of a contemporary, poetic innovator. And although it does serve to flesh out his career trajectory, Adventures of Pi also offers readers engaging moments wherein the poet confronts the racial fissures in then-contemporary America in a straightforward but aesthetically compelling manner. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from his poem “White Noise (Fighting to Wake Up)”:

Similarly, racial and cultural issues are addressed and challenged throughout the collection in poems such as “A Black Man Who Wants to be a White Woman” and “How Do I Cross Out the X Malcom.” Within these poems, Williams creates linguistic spaces wherein he’s “Scribabbling” his words into an “estranged language” (34) of neologism and wordplay in order to write a:

Here's a video clip of Williams reading his poem "Mayhem" from The Hero Project of the Century:

The final event of the semester for the Poets of Ohio reading series will take place on Thursday, 10 April when the poet Larissa Szporluk will visit Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH.

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:

Yesterday, the poet and critic Tyrone Williams traveled from Cincinnati to Cleveland in order to read and discuss his poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt from my introduction, along with a video clip from the event:In late-2002, I began actively exploring the world of contemporary poetry. As a way to discover the names of poets, presses, and different aesthetics that interested me, I started reading pretty much any literary journal I could get my hands on. After a few months of scouring the small press and magazine section at Tattered Cover in downtown Denver, I found myself gravitating toward journals such as The Canary, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, Open City, and Verse.

In one of these magazines, the Fall/Winter 2003 issue of Fence, an article by Rodeny Phillips appeared that was titled “Exotic flowers, decayed gods, and the fall of paganism: The 2003 Poets House Poetry Showcase, an exhibit of poetry books published in 2002.” In addition to providing a comprehensive overview of the showcase, several sidebars located in the article’s margins offered “Best Of” lists: “Best Books of Experimental Poetry” and “Best Debut Collections,” for example. While each list contained a series of names and titles with which I was unfamiliar—but, subsequently, over the years would become intimately familiar—one name caught my attention due to the fact that it found its way onto no less than three of these lists (if my memory serves me correctly): Tyrone Williams and his first book c.c., published by Krupskaya Press.

Given that the Phillips' article championed this poet and collection to such a high degree, I went online and ordered a copy. When the book finally arrived and I read through it, I was confronted with a style of poetry that was theretofore unknown to me. The writing in Williams’ first book employed radical notions of form, citation, appropriation, and marginalia, all the while remaining socially, politically, and culturally engaged. This, indeed, was not the type of poetry I had previously encountered (even with exposure to the High Modernists); no, this was something more daring, complex, and exciting. The poems of c.c., such as “Cold Calls,” “I am not Proud to be Black,” and “TAG” were avant-tour de forces that acted as catalysts for my own interest, involvement, and dedication to poetry over the course of the next twelve years.

In 2008, Omnidawn Publishing released Williams’ second book of poetry On Spec, which I would later use for my comprehensive exams as I pursued my doctorate. In a citation of his book that I wrote in 2010, I argued that the collection “explores the confluence of post-Language poetry and African-American poetic tradition” by entwining “diverse aesthetic and ideological lineages” through the use of “different idioms and whose contents are often thought to be at odds with one another.” Moreover, I noted the book’s “conflation of genres,” wherein the poems sought to “question the relationship between theory and poetry,” as well as drama; in doing so, Williams created a “transitional and often nebulous zone.” These “boundary-defying techniques” were further highlighted in his “use of check-boxes, errata and footnotes…mathematical equations, cross-outs, quotation, and liberal use of white space.”

Most recently, his 2011 collection Howell (Atelos Press), which is a reference to Howell, Michigan and conceived in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, is an epic “writing through” of history that extends to nearly 400 pages in length.

For our course this semester, though, we read Williams’ Adventures of Pi: Poems 1980-1990. The collection takes a backward glance at the poet’s work, thus functioning as an interesting prequel in the development of a contemporary, poetic innovator. And although it does serve to flesh out his career trajectory, Adventures of Pi also offers readers engaging moments wherein the poet confronts the racial fissures in then-contemporary America in a straightforward but aesthetically compelling manner. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from his poem “White Noise (Fighting to Wake Up)”:

of a body dreaming two dreams,The notion that two dreams and two Americas exist within the speaker echoes, at least to me, the concept of double-consciousness as proposed by W.E.B. DuBois in The Souls of Black Folk, in which he famously wrote:

only one of which is called

a black man in America,

the other, America

itself (18)

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.Furthermore, the form of Williams’ poem suggests an intensification of this “two-ness” through a strategic use of a stanza break between the two instances of “America” within the single, syntactical unit. In this sense, the poem fuses form and content in order to heighten its underlying conceptual framework.

Similarly, racial and cultural issues are addressed and challenged throughout the collection in poems such as “A Black Man Who Wants to be a White Woman” and “How Do I Cross Out the X Malcom.” Within these poems, Williams creates linguistic spaces wherein he’s “Scribabbling” his words into an “estranged language” (34) of neologism and wordplay in order to write a:

story we make up about the other storiesYes, stories made up of stories compound by other stories, all constructing an American narrative that resonates with the “Remarkable violence” inherent to the history of a country fraught with civil rights’ tensions and complex racial relations. But far from simply being a collection of didactic poems, Williams employs his heightened intellect, aesthetic sensibilities, and ear for the musical phrase in order to compose poems that address the political and social worlds while simultaneously providing aesthetic pleasures. In doing so, the poems challenge both our understanding of contemporary poetry and our concept of race in America today.

[Which] Itself is made up of other stories:

Thus the three dimensions of history—plus history,

Remarkable violence (34)

Here's a video clip of Williams reading his poem "Mayhem" from The Hero Project of the Century:

The final event of the semester for the Poets of Ohio reading series will take place on Thursday, 10 April when the poet Larissa Szporluk will visit Case Western Reserve University from Bowling Green, OH.

Bloomfield, Foley, and Xu Read Poems

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard Today: Bloomfield, Foley, and Xu" at Vouched Books on 20 March 2014.

Last night the poets Luke Bloomfield, Brian Foley, and Wendy Xu passed through Cleveland, OH on their Moonbucket reading tour in promotion of their books Russian Novels (Factory Hollow Press, 2014), The Constitution (Black Ocean, 2014), and You Are Not Dead (Cleveland State Poetry Center, 2013), respectively. Below are three short video clips of each poet performing at the event, which took place at Guide to Kulchur.

Here's Luke Bloomfield reading his poem "Fisticuffs":

Here's Brian Foley reading his poem "Acumen":

Here's Wendy Xu reading here poem "Nocturne":

Their tour, which has also taken them to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Akron, will continue tonight in Buffalo, NY.

Last night the poets Luke Bloomfield, Brian Foley, and Wendy Xu passed through Cleveland, OH on their Moonbucket reading tour in promotion of their books Russian Novels (Factory Hollow Press, 2014), The Constitution (Black Ocean, 2014), and You Are Not Dead (Cleveland State Poetry Center, 2013), respectively. Below are three short video clips of each poet performing at the event, which took place at Guide to Kulchur.

Here's Luke Bloomfield reading his poem "Fisticuffs":

Here's Brian Foley reading his poem "Acumen":

Here's Wendy Xu reading here poem "Nocturne":

Their tour, which has also taken them to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Akron, will continue tonight in Buffalo, NY.

Dave Lucas Introduction

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Dave Lucas" at Vouched Books on 10 March 2014.

After a month-long layoff, the Poets of Ohio reading series resumed, hosting Cleveland-native Dave Lucas. Lucas read and discussed poems from his debut-collection Weather (University of Georgia Press, 2011) to a large, hometown crowd last night at Case Western Reserve University. Below is an excerpt of the introduction I gave for the event:

After a month-long layoff, the Poets of Ohio reading series resumed, hosting Cleveland-native Dave Lucas. Lucas read and discussed poems from his debut-collection Weather (University of Georgia Press, 2011) to a large, hometown crowd last night at Case Western Reserve University. Below is an excerpt of the introduction I gave for the event:

The history of poetry in and of Cleveland is fraught with complex tensions between poet and city. In a letter dated 15 June 1922, Hart Crane, arguably Cleveland’s most famous poet, wrote to his friend Wilbur Underwood that “Life is awful in Cleveland.” In the recently published anthology of his writing, the poet Russell Atkins focuses his creative imagination on the “miserabled gone” of Cleveland and its images of the “sick / against [the] broken.”And, d.a. levy, another local yet nationally-known poet, wrote:

Dave Lucas’ first book, Weather, I think, traffics primarily in this latter category. While the speakers of his poems do acknowledge the “dying arts” (1) and the “muddy unmarked grave[s]” (14) of industrialism, they also articulate a relentless determination by the city and its inhabitants to persevere. For instance, in the poem “River on Fire,” Lucas meditates upon the burning of the Cuyahoga River, concluding with the realization that the “river burned and was not consumed” (15). Yes, it was set aflame several times—13 times, to be exact, from 1868 to 1969—but the river remains. And now, due to recent environmental efforts, the Cuyahoga is cleaner than it has ever been during the past 150 years.

In an interview I conducted with Lucas a little over a year ago, he mentioned that he hoped the poems of Weather would work through the tired narratives of “apocalypse and exodus” that so often dictate conversations about Cleveland in order to “transform” our collective imagination of and about the city. Rather than an urban landscape of decay, the poet wants “both [his] art and [his] city to be…in the present tense”: alive, vibrant, and worthy of praise.

To this extent, then, the poems of Weather mirror rather closely the poet Richard Hugo’s concept of the “triggering town,” wherein the “initiating subject”—in this case, Cleveland—activates the “imagination” in order to yolk intellectual curiosity, emotional resonance, and aesthetic beauty at the site of the poem.

Yes, the poem becomes a place both to embody and honor another place; and this doubling of place within Weather serves as a poetic reminder that Cleveland is not dead. Instead, the city is, indeed, “present” and thrives in our presence; perhaps under a layer of rust, for sure, but it lives and flourishes, exuding a passionate intensity that belies the negative critiques outsiders so often foist upon our city.

Here’s a video of Lucas reading his poem “Midst of a Burning Fiery Furnace” from the event:

This Thursday, 20 March, the poet Daniel Tiffany will deliver a hybrid reading-lecture titled "Is Kitsch Still a Dirty Word?"; and on Thursday, 27 March, the poet Tyrone Williams will read and discuss his poetry. Both events will be held on Case Western Reserve University's campus.

After a month-long layoff, the Poets of Ohio reading series resumed, hosting Cleveland-native Dave Lucas. Lucas read and discussed poems from his debut-collection Weather (University of Georgia Press, 2011) to a large, hometown crowd last night at Case Western Reserve University. Below is an excerpt of the introduction I gave for the event:

After a month-long layoff, the Poets of Ohio reading series resumed, hosting Cleveland-native Dave Lucas. Lucas read and discussed poems from his debut-collection Weather (University of Georgia Press, 2011) to a large, hometown crowd last night at Case Western Reserve University. Below is an excerpt of the introduction I gave for the event:The history of poetry in and of Cleveland is fraught with complex tensions between poet and city. In a letter dated 15 June 1922, Hart Crane, arguably Cleveland’s most famous poet, wrote to his friend Wilbur Underwood that “Life is awful in Cleveland.” In the recently published anthology of his writing, the poet Russell Atkins focuses his creative imagination on the “miserabled gone” of Cleveland and its images of the “sick / against [the] broken.”And, d.a. levy, another local yet nationally-known poet, wrote:

cleveland, i gave youWhile, no doubt, it’s easy to promote a narrative of Cleveland within poetry and the arts that is filtered through such a negative lens; there also exists an alternate vision that forwards a place-based poetics which champions the city in all its oxidized glory.

the poems that no one ever

wrote about you

and you gave me

NOTHING

Dave Lucas’ first book, Weather, I think, traffics primarily in this latter category. While the speakers of his poems do acknowledge the “dying arts” (1) and the “muddy unmarked grave[s]” (14) of industrialism, they also articulate a relentless determination by the city and its inhabitants to persevere. For instance, in the poem “River on Fire,” Lucas meditates upon the burning of the Cuyahoga River, concluding with the realization that the “river burned and was not consumed” (15). Yes, it was set aflame several times—13 times, to be exact, from 1868 to 1969—but the river remains. And now, due to recent environmental efforts, the Cuyahoga is cleaner than it has ever been during the past 150 years.

In an interview I conducted with Lucas a little over a year ago, he mentioned that he hoped the poems of Weather would work through the tired narratives of “apocalypse and exodus” that so often dictate conversations about Cleveland in order to “transform” our collective imagination of and about the city. Rather than an urban landscape of decay, the poet wants “both [his] art and [his] city to be…in the present tense”: alive, vibrant, and worthy of praise.

To this extent, then, the poems of Weather mirror rather closely the poet Richard Hugo’s concept of the “triggering town,” wherein the “initiating subject”—in this case, Cleveland—activates the “imagination” in order to yolk intellectual curiosity, emotional resonance, and aesthetic beauty at the site of the poem.

Yes, the poem becomes a place both to embody and honor another place; and this doubling of place within Weather serves as a poetic reminder that Cleveland is not dead. Instead, the city is, indeed, “present” and thrives in our presence; perhaps under a layer of rust, for sure, but it lives and flourishes, exuding a passionate intensity that belies the negative critiques outsiders so often foist upon our city.

Here’s a video of Lucas reading his poem “Midst of a Burning Fiery Furnace” from the event:

This Thursday, 20 March, the poet Daniel Tiffany will deliver a hybrid reading-lecture titled "Is Kitsch Still a Dirty Word?"; and on Thursday, 27 March, the poet Tyrone Williams will read and discuss his poetry. Both events will be held on Case Western Reserve University's campus.

Jennifer Moxley Reads "No Place Like"

Thi article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard This Week: Jennifer Moxley" at Vouched Books on 06 March 2014.

A couple of weeks ago, the poet Jennifer Moxley flew in from Maine to vist Case Western Reserve University's campus in Cleveland, OH.

On 20 February, she led a group discussion that focused on her article "A Deeper, Older O: The Oral (Sex) Tradition (in Poetry)," which is forthcoming in the Jeffrey Robinson and Julie Carr edited Active Romanticism, (University of Alabama Press, 2014).

The following day, Moxely read poems at an event, performing mostly new material that will appear in her forthcoming collection The Open Secret (Flood Editions, 2014).

Below is a video clip of the poet reading her poem "No Place Like":

To find more of Moxley's work, click-through to Flood Edition's website.

For those in the northeast Ohio area, Dave Lucas (03/18), Daniel Tiffany (03/20), and Tyrone Williams (03/27) will all read at Case later this month.

A couple of weeks ago, the poet Jennifer Moxley flew in from Maine to vist Case Western Reserve University's campus in Cleveland, OH.

On 20 February, she led a group discussion that focused on her article "A Deeper, Older O: The Oral (Sex) Tradition (in Poetry)," which is forthcoming in the Jeffrey Robinson and Julie Carr edited Active Romanticism, (University of Alabama Press, 2014).

The following day, Moxely read poems at an event, performing mostly new material that will appear in her forthcoming collection The Open Secret (Flood Editions, 2014).

Below is a video clip of the poet reading her poem "No Place Like":

To find more of Moxley's work, click-through to Flood Edition's website.

For those in the northeast Ohio area, Dave Lucas (03/18), Daniel Tiffany (03/20), and Tyrone Williams (03/27) will all read at Case later this month.

Abide

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Read This Month: Abide" At Vouched Books on 03 March 2014.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

After recently receiving a copy of his posthumously released Abide (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014) in the mail, I was thankful for the opportunity to read new work by him; but that thankfulness was tempered by the sadness of knowing that he is no longer with us.

Abide serves to reinforce these conflicted feelings. On the one hand, the poems demonstrate York’s deft musicality, attention to craft, and adherence to an ethical imperative that originates in the historicity and spirit of the Civil Rights movement. On the other hand, the elegies therein resonant with sadly, prophetic echoes that often times seem to prefigure his own passing.

The poem “Mayflower,” for instance, is an elegy composed for John Earl Reese, who the poem’s dedication mentions was a “sixteen-year-old, shot by Klansmen through the window of a café” on “October 22, 1955.” The opening lines read:

As the poem proceeds, the speaker eventually levels an awful truth:

And one can only assume that York had much more to say. In the book’s concluding “Foreword to a Subsequent Reading,” Jake writes that his project of creating poetic monuments to the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement was, indeed:

To this end, York understood the necessary connection between memory and naming bound within breath: “We visit memory sites…but if memory lives on there, it isn’t memory anymore. Memory lives in the breath we breathe, in the air we make together” (80). We should, then, take this to declaration of breath to heart in order to keep both the memory of Civil Rights’ martyrs and York alive.

To do so, though, requires more than a visit to the physical site of a memorial or purchasing a book artifact. Rather, we must sing the names of the deceased through the silences. We must voice the names and recite aloud the poems, such that we begin “reaching / for the sound of some beyond” in order to create a “vibration” (8) that awakens the spirits and brings them to life through the audible word. Doing so will, in the end, reactivate the “Last breaths of the disappeared” (36) at and in the site of the poem. Or, as Jake himself wrote:

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.

From 2004-2005, I was a graduate student of Jake Adam York’s at University of Colorado-Denver; I also worked as a poetry editor with him on some early issues of Copper Nickel. Having known Jake personally and being familiar with his dedication to and enthusiasm for all-things poetry, it was heartbreaking to hear of his untimely death just over one year ago.After recently receiving a copy of his posthumously released Abide (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014) in the mail, I was thankful for the opportunity to read new work by him; but that thankfulness was tempered by the sadness of knowing that he is no longer with us.

Abide serves to reinforce these conflicted feelings. On the one hand, the poems demonstrate York’s deft musicality, attention to craft, and adherence to an ethical imperative that originates in the historicity and spirit of the Civil Rights movement. On the other hand, the elegies therein resonant with sadly, prophetic echoes that often times seem to prefigure his own passing.

The poem “Mayflower,” for instance, is an elegy composed for John Earl Reese, who the poem’s dedication mentions was a “sixteen-year-old, shot by Klansmen through the window of a café” on “October 22, 1955.” The opening lines read:

Before the bird’s songWhile, certainly, one can read the passage on the surface level as a lament for Reese’s passing, it is not difficult—at least for this reader—to read these lines as premonitory: “Before the bird’s song,” or the release of the poems in Abide, all we can “hear” from York is the “quiet” or “silence” following his death. Upon publication, the effects of his death become “part of the song,” at least to the extent that the poet’s absence can be keenly felt (or read) in all of these poems.

you hear its quiet

which becomes part of the song

and lives on after,

struck notes bright

in silence (17)

As the poem proceeds, the speaker eventually levels an awful truth:

and a young man’s voiceYes, in the poems of Abide we hear the “young man’s voice” singing for us once more; but inherent to this music is the realization that the collection will be followed by the “young’s man’s / silence” and “all // he [will] not say.”

becomes a young man’s

silence, all

he did not say (18)

And one can only assume that York had much more to say. In the book’s concluding “Foreword to a Subsequent Reading,” Jake writes that his project of creating poetic monuments to the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement was, indeed:

always too big for one book. It is more complicated than a simple serial form, like a trilogy. It is the work of a life, both countless and one; one cannot predict how long it will take, but it will take as long as it will take. Abide continues, advances, event as it contains, as it remains. (79)While the completion of his project might not have reached full fruition, the four books York released do serve to “elegize” at least some of the “men, women, and children who were martyred between 1954 and 1968 as part of the freedom to struggle” (79) in a beautiful and earnest manner. Such elegies, it would appear, stem from both explicit and implicit prohibitions against articulating and celebrating these victims. Or, as the poem “Letter to be Wrapped around a 12-Inch Disc” states:

We had so muchYork’s poems, specifically the elegies, seek to rupture the “silence” by stirring up and remembering those names that others wanted to be left behind and forgotten in the forward march of history.

behind us, the history

we were told we shouldn’t

name, stir up, remember,

so much silence

we needed to break (11)

To this end, York understood the necessary connection between memory and naming bound within breath: “We visit memory sites…but if memory lives on there, it isn’t memory anymore. Memory lives in the breath we breathe, in the air we make together” (80). We should, then, take this to declaration of breath to heart in order to keep both the memory of Civil Rights’ martyrs and York alive.

To do so, though, requires more than a visit to the physical site of a memorial or purchasing a book artifact. Rather, we must sing the names of the deceased through the silences. We must voice the names and recite aloud the poems, such that we begin “reaching / for the sound of some beyond” in order to create a “vibration” (8) that awakens the spirits and brings them to life through the audible word. Doing so will, in the end, reactivate the “Last breaths of the disappeared” (36) at and in the site of the poem. Or, as Jake himself wrote:

Maybe we keep sayingAnd, indeed, by reciting the poems of Abide aloud while reading, the reader shapes York's voice within their own voice, such that the poet's memory haunts the lungs of another, imbuing the breath and body with the spirit of the deceased.

their silences between our words,

the shape of their voices

in ours, in ours

the warmth that haunts

their absent lungs. (34)

Best Poems

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Read Today: Best Poems" at Vouched Books on 24 February 2014.

Recently, Big Lucks (in conjunction with Narrow House Editions) published its first, official release: Mike Krutel’s chapbook Best Poems.

Recently, Big Lucks (in conjunction with Narrow House Editions) published its first, official release: Mike Krutel’s chapbook Best Poems.

The poems in Krutel’s chapbook (which is, incidentally, his first, official release as well) wander from line to line and image to image in strange, half-lit worlds; or, as the speaker of “Best Picture of Me in a Tub of Rotary Phones” says:

Of course, why would you want to escape? Because, indeed, getting lost within these poems ends up being a lot of fun. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the collection’s first poem, simply titled “Best”:

While they might concede to (or revel in) their waywardness, the speakers of these poems continually attempt to make sense of their worlds as they are led further astray by the night. And that sense comes by way of internal arrangement or some abstract, organizing principles of the poems; we're told as much in the following passages:

Recently, Big Lucks (in conjunction with Narrow House Editions) published its first, official release: Mike Krutel’s chapbook Best Poems.

Recently, Big Lucks (in conjunction with Narrow House Editions) published its first, official release: Mike Krutel’s chapbook Best Poems.The poems in Krutel’s chapbook (which is, incidentally, his first, official release as well) wander from line to line and image to image in strange, half-lit worlds; or, as the speaker of “Best Picture of Me in a Tub of Rotary Phones” says:

You keep me waiting,Yes, Best Poems often reads as if it were the secret dream journal of a somnambulist “Wandering” through “worlds” filled with words; and in this world of language, both the speaker and the reader become lost in a playful labyrinth of “mirrors” so that they “don’t know / where to turn” in order to escape.

grown man that sleepwalks his

way down a well to linger. Wandering

full of worlds. I don’t know

where to turn or if there’s any

way out of this mirror. (22)

Of course, why would you want to escape? Because, indeed, getting lost within these poems ends up being a lot of fun. Take, for instance, the opening lines of the collection’s first poem, simply titled “Best”:

Tonight is night of no sleep.Like the somnambulist before him, the insomniac in the “night of no sleep” encounters an equally strange, half-lit world during the hour of the wolf. Haunted by both the surreal (e.g. “dandelions screaming”) and the mundane (e.g. “The cats rubs a glass frame”), the sleepwalker and the sleepless, the speaker and the reader, all become “comfortably lost / inside a small idea,” a small image, and a small world made up of the “sound outside” ourselves.

Cannonballs over the playground.

The cat rubs a glass frame off the mantle.

Somewhere there is a woman, comfortably lost

inside a small idea. You are that woman

and above you are your own best guesses.

How the vehicles are doing real things.

How the sun shoots its umbilical light around,

straight into night. There is sound outside.

It could be dandelions screaming

like engines or the causeways between

us. You are a small woman. I am holding

these individually wrapped letters

between the scaffold of my ribcage. All indications

say I should know better by now. (1)

While they might concede to (or revel in) their waywardness, the speakers of these poems continually attempt to make sense of their worlds as they are led further astray by the night. And that sense comes by way of internal arrangement or some abstract, organizing principles of the poems; we're told as much in the following passages:

I am with difficultyOf course, these and other “requirements for adequate reintegration” (14) are, perhaps, a bit of a dodge. For, in fact, if they serve a determinate purpose, it is not actually to access sense or plan an escape; rather, these alternate arrangements serve to ratchet up the playfulness of these poems, which, at night, glow beneath the “ambiguous moon” as it “does its dirty thing” (10).

rearranging patterns of static

that ferment around

our little heads. (10)

…

The moment became always

a reassembly of everything

different from everything, which is was. (21)

Jeff Alessandrelli Interview

This article first appeared as a post titled "Awful Interview: Jeff Alessandrelli" at Vouched Books on 17 February 2014.

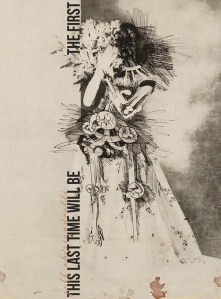

I've written about my friend and poet Jeff Alessandrelli's work before; but with the release of his new, full-length collection of poetry This Last Time Will Be the First Time (Burnside Review Books, 2014), I thought I'd ask him some in-depth questions about his poetry and writing in preparation for its release. Jeff was kind enough to answer my questions, via email, over the course of the past few week. (Head Voucher Laura Relyea also conducted an Awful Interview with Alessandrelli a couple years ago.) Below are the contents of that exchange:

I've written about my friend and poet Jeff Alessandrelli's work before; but with the release of his new, full-length collection of poetry This Last Time Will Be the First Time (Burnside Review Books, 2014), I thought I'd ask him some in-depth questions about his poetry and writing in preparation for its release. Jeff was kind enough to answer my questions, via email, over the course of the past few week. (Head Voucher Laura Relyea also conducted an Awful Interview with Alessandrelli a couple years ago.) Below are the contents of that exchange:

“People Are Places Are Places Are People” is the opening section of your new book This Last Time Will Be the First Time. The title of each poem in this section either invokes the name of a person (usually an artist or writer), or employs direction quotation by them. I wonder if you could address the use of proper nouns in these titles. Likewise, what is the relationship between people and places? Finally, how do you understand these names creating a continuum or lineage of influence for you as a writer and artist?

With regards to your initial question— most of the poems in This Last Time Will Be The First's first section were, directly and indirectly, inspired by my interest in history; I’m fascinated by the (often, but not always, traumatic) lives of the writers/artists I most admire— Evel Knievel (who during his lifetime broke 433 bones, a Guinness World Record), Lenny Bruce (who, about his heroin abuse, said I’ll die young but it’s like kissing God), Anne Carson (whose work as a cultural historian for me is as important, if not more so, than her work as a purely creative writer—although the argument could be made that both modes of her writing are essentially one and the same) and Eileen Myles (Eileen Myles rules). That being said, most of the poems in “People Are Places Are Places Are People” are 90% imagination-based, 10% history-based. In my own work the historical is the jumping off point for the creative; I’m not a historian by any common definition of the word.

The relationship between people and places and places and people— like most easy thinking members of society, I often associate people (Gertrude Stein, say) with places (1920’s Paris). But I also think that where one lives—by choice or circumstance—does become who one is; our environments are our identities, whether we relish or hate that fact.

As far as influence, specifically in terms of my own development as a writer/artist – I consider myself a reader first and a writer second. I read all sorts of stuff— fiction and poetry predominantly but also a healthy amount of history (primarily ancient, weird stuff), oral biographies and arcane “factoid” stuff. And have you been on the internet? There’s a grip of stuff stuck in there, some of it even worth reading. All of which is to say that for me influence is something that suffuses every aspect of my writing. I don’t honestly consider myself to be a particularly “original” or “groundbreaking” poet. But what I do think I’m good at is melding different linguistic particles, often found in wildly different places, into one static thing that I subsequently deem a “poem.”

One of my favorite writers is David Markson, who wrote a series of books toward the end of his life that were almost entirely composed of artistic and cultural anecdotes and quotes (i.e. “A seascape by Henri Matisse was once hung upside down in the Museum of Modern Art in New York—and left that way for a month and a half;” “Art is not truth. Art is a lie that enables us to recognize truth”—Pablo Picasso). I personally find Markson’s work to be far more interesting (and “original,” to use that word again) than a wholly fictional novel about the emotional complications parental divorce engenders in a 19 year old growing up in rural Indiana or a wholly fictional novel about ketamine addiction or a wholly fictional novel about an overweight Turkish bombardier fighting in World War I. (I’m making all those up, by the way. Although I’m sure they’ve also already been written.)

As a writer I’m far more interested in reading than in writing. But the great writers don’t let you simply read their work. They make you rewrite it.

I like that you mention “identities” in your previous answer because the concept segues nicely into a question about the second section of your book: “Jeffrey Roberts’ Dreamcoats.” How does the character Jeffrey Roberts align with or diverge from Jeffrey Alessandrelli? I mean, “Roberts” is your middle name, correct? You certainly seem to be toying with the concept of self-identification, autobiography, and confession--but, no doubt, in a off-kilter manner--given a title like “The Semi-biography of Jeffrey Roberts.” Tell me more about the partial identity inherent to the “semi” modifier. How do the poems in this section trouble our notions of selfhood and subjectivity?

Although my middle name is Robert—and, since my last name is so long (13 letters!), Jeffrey Roberts is the name I usually give at restaurants/bars when I’m waiting for a table—the poems in “Jeffrey Roberts’ Dreamcoats” are only very very loosely related to myself. The only similarities, actually, reside in the fact that both Jeffrey Roberts and I hate job interviews and once also had to work fairly diligently on doctoral dissertations. But re: identity and selfhood, both partial and not, the character (or speaker) Jeffrey Roberts is not a stand-in for the author Jeff Alessandrelli. I don’t consider myself particularly interesting, and in light of that opinion I (rightly or wrongly) rarely write out of direct personal experience. The last poem of the section, “The Same Jeffrey Roberts That Has Been Missing” begins with the line, “I was born with two wings, / one of them broken.” Broken or not, I wish I had been born with wings. Are you familiar with the Nora Ephron directed film Michael (1996)? Playing the Archangel Michael, John Travolta had wings. It wuz tight.

When Stephen Malkmus' first solo album came out, Magnet did an exposé on him. In that article, the reporter asked Malkmus if he ever wrote songs about himself; he replied:

I do agree/identify with Malkmus’s statement, yes. And I’d also say that identification is less about my writing and more about my personality—regardless of the situation, I don’t much like to talk about myself. (Job interviews are tough.) Which thus means I rarely find myself writing (directly at least) about myself; instead, I’d rather “make things up” or identify fissures in language that I find interesting and then exploit them to my own ends. I’m sure there’s some deep-seated Freudian shit that I should consider finding out re: why I don’t like to write about myself very often, but in the end I’d say I’m simply more engaged in fiction than reality. And I don’t find my personal reality—day in, day out—to be necessarily worthy of poetic effort. There’s more out there and poem after poem I’m hoping to find it out.

As for Keats’ quote, I’d say that I identify with it as well. Although I also find a bit sad— the fact that in order to embody something one has to, to a degree at least, reject their own idiosyncratic existence, gives me a minor case of the willies.

One of my main goals in life is to complete eradicate my own self-absorption. It’s something that I feel very strongly about. It’s also something that—as a writer at least—I think is impossible pretty much.

I like the idea of “fissures in language,” at least to the extent that is conjures in my mind an image of you (or James Franco) as Aaron Raslton hacking away at your arm with a penknife in order to extricate yourself from a deep and narrow poetry crevice. But something tells me that’s not what you mean. Could you explain a bit further about these linguistic fissures? Likewise, could you talk about some specific examples from your new book?

I simply mean parts of language that we take for granted or perhaps don’t think much about, parts that are thus apt for poetic manipulation. Like how little words are engrained in so many big words— is the art in party the art in heart the art in fart the same art in Stuttgart? Or the ass in crass the same ass in passion the same ass in association? I don’t know—maybe that’s stupid or facile, but I find it kinda interesting. In “(Sharks),” a poem in the 3rd section of This Last Time Will Be The First, I write how “I hope to be creatively satisfied// in the same manner as the windmill/ and jetstream.” Which in and of itself doesn’t say or mean a whole lot probably—but I personally find the whole concept of “creative satisfaction” to be strange. Sexual satisfaction I can understand. I can understand gustatory satisfaction and monetary satisfaction. Maybe even spiritual satisfaction. But “creative satisfaction” is something that I find alien, possibly because to be “creative” in any field means, to me at least, to be continually hungry for more. Cr-eat-ive.

Also, I am not a linguist. Obviously.

The lack of satisfaction you derive from the creative process makes me think about the repetitions in your collections. By that, I mean, there's a passage in the poem “Simple Question” from your “little book” Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound (Ravenna Press, 2011) that states:

I mean, I derive satisfaction from the creative process, definitely—it’s just that I don’t derive the same type of satisfaction as those other kinds I mentioned, mostly because I think being “creatively satisfied” is somewhat of an oxymoron; if you’re 100% “creatively satisfied” then I think you either have too much confidence in your work or need to move somewhere else pretty quickly. A plethora of satisfaction for writers/artists/thinkers in general is a trap and one that, in my opinion, can beget some potentially boring crap. The short, more readily known title of the song is “Satisfaction” but the longer version is “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Sure, they’re mostly talking about sex, but I think if Mick J. and Keith R. had been totally content and “creatively satisfied” that (inarguably iconic) song wouldn’t have come out the way it did musically or lyrically.

As for my own personal poetic repetition/ re-appropriation—something that I do fairly infrequently— it doesn’t signal a dissatisfaction with the original permutation at all; the opposite actually. Years ago my friend Trey told me that the poet Donald Revell has, in wildly different poems, the same exact stanza (identical line breaks and everything) in something like 4 or 5 of his books. And when asked about it he (I’m paraphrasing, obviously) said, “Yeah, I really like that stanza.” I did and do think that’s great. In both of those poems I’m paying homage to the creativity of Erik Satie and Barbara Guest, both of whom, in my opinion, had pretty wild imaginations. I liked the way I said it the first time, so I thought I’d try it again. I love leftovers. I love second (and sometimes even third) helpings.

That all being said, is the recycling of my own lines an example of extreme “creative satisfaction?” I’m not sure. But probably. Forget remembering.

The penultimate section of your new book is a longer poem in parts, titled “It’s Especially Dangerous To Be Conscious of Oneself.” Did you conceive of this poem, initially, as one extend piece, or did you end up putting individual pieces together retroactively? What, for you, does the long/serial/sequential poem offer that a “regular” of “small-sized” poem does not? And, of course, why is it especially dangerous to be conscious of oneself?

I started writing that poem in early 2011 and the earliest version of it appeared in Octopus Magazine later that year; a 2nd, different version of it subsequently appeared in a chapbook entitled Don’t Let Me Forget To Feed The Sharks published in early 2012. And then there’s the version in the book, which is wildly different than the other iterations and really only loosely connected to them. Throughout, though, the main thematic “thread,” as it were, is the poem’s epigraph, which is taken from (as translated by A.C. Graham) The Book of Lieh- tz'u: A Classic of Tao and reads:

As for the serial poem structure, I think it can force a writer to make (imagistic, thematic, emotional, associational, linguistic, etc.) connections in his/her work that singular poems, obviously, don’t allow for. But it’s not my ideal form and in my opinion somewhat overused in contemporary poetry. I personally believe it’s far more difficult to write a long poem with direct/overt threads than it is to write a serial poem with threads only loosely woven together.

It is especially dangerous to be conscious of oneself because the more conscious you are of yourself the less conscious you are of everything and everyone else. “A gambler plays better for tiles than for money, because he does not bother to think; a good swimmer learns to handle a boat quickly, because he does not care if it turns over; a drunken man failing from a cart escapes with his life because, being unconscious, he does not stiffen himself before collision… A woman aware that she is beautiful ceases to be beautiful,” etc. Being too conscious (or aware or engrossed or absorbed) of yourself inevitably means you’re not conscious of what else is out there. Which is a lot. And the title of that poem sums up the way I desire to live and be—something I’m still working on, of course.

I've written about my friend and poet Jeff Alessandrelli's work before; but with the release of his new, full-length collection of poetry This Last Time Will Be the First Time (Burnside Review Books, 2014), I thought I'd ask him some in-depth questions about his poetry and writing in preparation for its release. Jeff was kind enough to answer my questions, via email, over the course of the past few week. (Head Voucher Laura Relyea also conducted an Awful Interview with Alessandrelli a couple years ago.) Below are the contents of that exchange:

I've written about my friend and poet Jeff Alessandrelli's work before; but with the release of his new, full-length collection of poetry This Last Time Will Be the First Time (Burnside Review Books, 2014), I thought I'd ask him some in-depth questions about his poetry and writing in preparation for its release. Jeff was kind enough to answer my questions, via email, over the course of the past few week. (Head Voucher Laura Relyea also conducted an Awful Interview with Alessandrelli a couple years ago.) Below are the contents of that exchange:“People Are Places Are Places Are People” is the opening section of your new book This Last Time Will Be the First Time. The title of each poem in this section either invokes the name of a person (usually an artist or writer), or employs direction quotation by them. I wonder if you could address the use of proper nouns in these titles. Likewise, what is the relationship between people and places? Finally, how do you understand these names creating a continuum or lineage of influence for you as a writer and artist?

With regards to your initial question— most of the poems in This Last Time Will Be The First's first section were, directly and indirectly, inspired by my interest in history; I’m fascinated by the (often, but not always, traumatic) lives of the writers/artists I most admire— Evel Knievel (who during his lifetime broke 433 bones, a Guinness World Record), Lenny Bruce (who, about his heroin abuse, said I’ll die young but it’s like kissing God), Anne Carson (whose work as a cultural historian for me is as important, if not more so, than her work as a purely creative writer—although the argument could be made that both modes of her writing are essentially one and the same) and Eileen Myles (Eileen Myles rules). That being said, most of the poems in “People Are Places Are Places Are People” are 90% imagination-based, 10% history-based. In my own work the historical is the jumping off point for the creative; I’m not a historian by any common definition of the word.

The relationship between people and places and places and people— like most easy thinking members of society, I often associate people (Gertrude Stein, say) with places (1920’s Paris). But I also think that where one lives—by choice or circumstance—does become who one is; our environments are our identities, whether we relish or hate that fact.

As far as influence, specifically in terms of my own development as a writer/artist – I consider myself a reader first and a writer second. I read all sorts of stuff— fiction and poetry predominantly but also a healthy amount of history (primarily ancient, weird stuff), oral biographies and arcane “factoid” stuff. And have you been on the internet? There’s a grip of stuff stuck in there, some of it even worth reading. All of which is to say that for me influence is something that suffuses every aspect of my writing. I don’t honestly consider myself to be a particularly “original” or “groundbreaking” poet. But what I do think I’m good at is melding different linguistic particles, often found in wildly different places, into one static thing that I subsequently deem a “poem.”

One of my favorite writers is David Markson, who wrote a series of books toward the end of his life that were almost entirely composed of artistic and cultural anecdotes and quotes (i.e. “A seascape by Henri Matisse was once hung upside down in the Museum of Modern Art in New York—and left that way for a month and a half;” “Art is not truth. Art is a lie that enables us to recognize truth”—Pablo Picasso). I personally find Markson’s work to be far more interesting (and “original,” to use that word again) than a wholly fictional novel about the emotional complications parental divorce engenders in a 19 year old growing up in rural Indiana or a wholly fictional novel about ketamine addiction or a wholly fictional novel about an overweight Turkish bombardier fighting in World War I. (I’m making all those up, by the way. Although I’m sure they’ve also already been written.)

As a writer I’m far more interested in reading than in writing. But the great writers don’t let you simply read their work. They make you rewrite it.

I like that you mention “identities” in your previous answer because the concept segues nicely into a question about the second section of your book: “Jeffrey Roberts’ Dreamcoats.” How does the character Jeffrey Roberts align with or diverge from Jeffrey Alessandrelli? I mean, “Roberts” is your middle name, correct? You certainly seem to be toying with the concept of self-identification, autobiography, and confession--but, no doubt, in a off-kilter manner--given a title like “The Semi-biography of Jeffrey Roberts.” Tell me more about the partial identity inherent to the “semi” modifier. How do the poems in this section trouble our notions of selfhood and subjectivity?

Although my middle name is Robert—and, since my last name is so long (13 letters!), Jeffrey Roberts is the name I usually give at restaurants/bars when I’m waiting for a table—the poems in “Jeffrey Roberts’ Dreamcoats” are only very very loosely related to myself. The only similarities, actually, reside in the fact that both Jeffrey Roberts and I hate job interviews and once also had to work fairly diligently on doctoral dissertations. But re: identity and selfhood, both partial and not, the character (or speaker) Jeffrey Roberts is not a stand-in for the author Jeff Alessandrelli. I don’t consider myself particularly interesting, and in light of that opinion I (rightly or wrongly) rarely write out of direct personal experience. The last poem of the section, “The Same Jeffrey Roberts That Has Been Missing” begins with the line, “I was born with two wings, / one of them broken.” Broken or not, I wish I had been born with wings. Are you familiar with the Nora Ephron directed film Michael (1996)? Playing the Archangel Michael, John Travolta had wings. It wuz tight.

When Stephen Malkmus' first solo album came out, Magnet did an exposé on him. In that article, the reporter asked Malkmus if he ever wrote songs about himself; he replied:

Not really. I’m always commenting or assuming voices about lives that would be interesting to me. I’m not particularly interested in my own feelings or my own struggles, so I wouldn’t write a song about them. But anything you write is a reflection on you, so if you are into being non-revealing, it shows your personality.Do you feel similarly? To you mind, what does it say about an artist if he/she avoids their own life as a source of material or inspiration? Likewise, your previous answer also reminds me of when John Keats wrote that:

the poet is the most unpoetical of anything in existence because he has no identity he is continually informing and filling some other body.Again, does this quote reflect, to some extent, your thoughts as well? Generally speaking, what type of relationship does a poet or a poem have with identity and subjectivity?

I do agree/identify with Malkmus’s statement, yes. And I’d also say that identification is less about my writing and more about my personality—regardless of the situation, I don’t much like to talk about myself. (Job interviews are tough.) Which thus means I rarely find myself writing (directly at least) about myself; instead, I’d rather “make things up” or identify fissures in language that I find interesting and then exploit them to my own ends. I’m sure there’s some deep-seated Freudian shit that I should consider finding out re: why I don’t like to write about myself very often, but in the end I’d say I’m simply more engaged in fiction than reality. And I don’t find my personal reality—day in, day out—to be necessarily worthy of poetic effort. There’s more out there and poem after poem I’m hoping to find it out.

As for Keats’ quote, I’d say that I identify with it as well. Although I also find a bit sad— the fact that in order to embody something one has to, to a degree at least, reject their own idiosyncratic existence, gives me a minor case of the willies.

One of my main goals in life is to complete eradicate my own self-absorption. It’s something that I feel very strongly about. It’s also something that—as a writer at least—I think is impossible pretty much.

I like the idea of “fissures in language,” at least to the extent that is conjures in my mind an image of you (or James Franco) as Aaron Raslton hacking away at your arm with a penknife in order to extricate yourself from a deep and narrow poetry crevice. But something tells me that’s not what you mean. Could you explain a bit further about these linguistic fissures? Likewise, could you talk about some specific examples from your new book?

I simply mean parts of language that we take for granted or perhaps don’t think much about, parts that are thus apt for poetic manipulation. Like how little words are engrained in so many big words— is the art in party the art in heart the art in fart the same art in Stuttgart? Or the ass in crass the same ass in passion the same ass in association? I don’t know—maybe that’s stupid or facile, but I find it kinda interesting. In “(Sharks),” a poem in the 3rd section of This Last Time Will Be The First, I write how “I hope to be creatively satisfied// in the same manner as the windmill/ and jetstream.” Which in and of itself doesn’t say or mean a whole lot probably—but I personally find the whole concept of “creative satisfaction” to be strange. Sexual satisfaction I can understand. I can understand gustatory satisfaction and monetary satisfaction. Maybe even spiritual satisfaction. But “creative satisfaction” is something that I find alien, possibly because to be “creative” in any field means, to me at least, to be continually hungry for more. Cr-eat-ive.

Also, I am not a linguist. Obviously.

The lack of satisfaction you derive from the creative process makes me think about the repetitions in your collections. By that, I mean, there's a passage in the poem “Simple Question” from your “little book” Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound (Ravenna Press, 2011) that states:

it is onlyAnd, in This Last Time Will Be The First, you have a poem titled “Understanding Barbara Guest” that contains the lines:

the imagination

that can resist

the imagination,

it is only

the imagination

that can withstand,

uphold, subvert

and resist

the imagination. (43)

It is onlyDoes the repetition or reuse of these words signal dissatisfaction with the original permutation? Or a dissatisfaction with the context in which it was originally found? If not, can you discuss what the recycling of your own lines means to you? How does returning to your previous poems for content/material affect your poetic sensibilities at both the moment of initial conception and the moment of re-appropriation?

the imagination

that can resist

the imagination,

it is only the imagination

that can withstand,

uphold, subvert

and resist

the imagination. (19)

I mean, I derive satisfaction from the creative process, definitely—it’s just that I don’t derive the same type of satisfaction as those other kinds I mentioned, mostly because I think being “creatively satisfied” is somewhat of an oxymoron; if you’re 100% “creatively satisfied” then I think you either have too much confidence in your work or need to move somewhere else pretty quickly. A plethora of satisfaction for writers/artists/thinkers in general is a trap and one that, in my opinion, can beget some potentially boring crap. The short, more readily known title of the song is “Satisfaction” but the longer version is “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Sure, they’re mostly talking about sex, but I think if Mick J. and Keith R. had been totally content and “creatively satisfied” that (inarguably iconic) song wouldn’t have come out the way it did musically or lyrically.

As for my own personal poetic repetition/ re-appropriation—something that I do fairly infrequently— it doesn’t signal a dissatisfaction with the original permutation at all; the opposite actually. Years ago my friend Trey told me that the poet Donald Revell has, in wildly different poems, the same exact stanza (identical line breaks and everything) in something like 4 or 5 of his books. And when asked about it he (I’m paraphrasing, obviously) said, “Yeah, I really like that stanza.” I did and do think that’s great. In both of those poems I’m paying homage to the creativity of Erik Satie and Barbara Guest, both of whom, in my opinion, had pretty wild imaginations. I liked the way I said it the first time, so I thought I’d try it again. I love leftovers. I love second (and sometimes even third) helpings.

That all being said, is the recycling of my own lines an example of extreme “creative satisfaction?” I’m not sure. But probably. Forget remembering.

The penultimate section of your new book is a longer poem in parts, titled “It’s Especially Dangerous To Be Conscious of Oneself.” Did you conceive of this poem, initially, as one extend piece, or did you end up putting individual pieces together retroactively? What, for you, does the long/serial/sequential poem offer that a “regular” of “small-sized” poem does not? And, of course, why is it especially dangerous to be conscious of oneself?

I started writing that poem in early 2011 and the earliest version of it appeared in Octopus Magazine later that year; a 2nd, different version of it subsequently appeared in a chapbook entitled Don’t Let Me Forget To Feed The Sharks published in early 2012. And then there’s the version in the book, which is wildly different than the other iterations and really only loosely connected to them. Throughout, though, the main thematic “thread,” as it were, is the poem’s epigraph, which is taken from (as translated by A.C. Graham) The Book of Lieh- tz'u: A Classic of Tao and reads:

There was a man who was born in Yen but grew up in Ch’u, and in old age returned to his native country. While he was passing through the state of Chin his companions played a joke on him. They pointed out a city and told him: “This is the capital of Yen.” He composed himself and looked solemn. Inside the city they pointed out a shrine: “This is the shrine of your quarter.” He breathed a deep sigh. They pointed out a hut: “This was your father’s cottage.” His tears welled up. They pointed out a mound: “This is your father’s tomb.” He could not help weeping aloud. His companions roared with laughter: “We were teasing you. You are still only in Chin.” The man was very embarrassed. When he reached Yen, and really saw the capital of Yen and the shrine of his quarter, really saw his father’s cottage and tomb, he did not feel it so deeply.Although each is, as mentioned, different, every version of “It Is Especially Dangerous To Be Conscious Of Oneself” takes as its primary feeling the emotionality (half ironic/half solemn and sincere) enveloped in that passage.

As for the serial poem structure, I think it can force a writer to make (imagistic, thematic, emotional, associational, linguistic, etc.) connections in his/her work that singular poems, obviously, don’t allow for. But it’s not my ideal form and in my opinion somewhat overused in contemporary poetry. I personally believe it’s far more difficult to write a long poem with direct/overt threads than it is to write a serial poem with threads only loosely woven together.

It is especially dangerous to be conscious of oneself because the more conscious you are of yourself the less conscious you are of everything and everyone else. “A gambler plays better for tiles than for money, because he does not bother to think; a good swimmer learns to handle a boat quickly, because he does not care if it turns over; a drunken man failing from a cart escapes with his life because, being unconscious, he does not stiffen himself before collision… A woman aware that she is beautiful ceases to be beautiful,” etc. Being too conscious (or aware or engrossed or absorbed) of yourself inevitably means you’re not conscious of what else is out there. Which is a lot. And the title of that poem sums up the way I desire to live and be—something I’m still working on, of course.

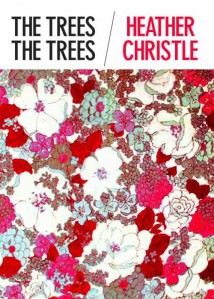

Heather Christle Introduction

This article first appeared as a post titled "Best Thing I’ve Heard/Read This Week: Heather Christle" at Vouched Books on 14 February 2104.

Yesterday evening, the poet Heather Christle drove to Cleveland from Yellow Springs, OH to read and discuss her poems at Case Western Reserve University for the Poets of Ohio reading series. Below is an excerpt of the introduction I gave for the event.