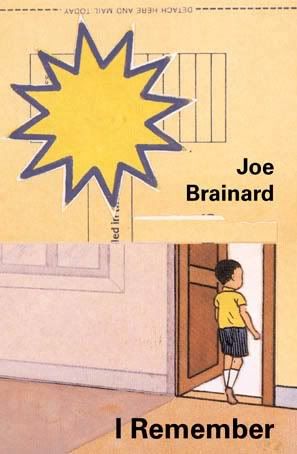

In 1971, Anne Waldman's Angel Hair Books published Joe Brainard's I Remember in an edition of 700 copies. After selling out, Angel Hair published an updated version titled More I Remember in 1972 and More I Remember More in 1973. In 1975, Full Court Press released a further revised and expanded edition that was later re-released by Granary Press and included a Ron Padgett penned afterword.

Brainard's book follows a simple but powerful constraint: write an extended series of sentences (and sometimes paragraphs), each one beginning with the anaphora “I remember...” The anaphoric refrain, coupled with the cataloging of memories suffused with mid-twentieth-century Americana necessarily draws comparison's to Walt Whitman. Indeed, I Remember certainly reads like “Song of Myself” updated for the mid-Twentieth Century.

For a better sense of Brainard's techniques, as well as the content he covers, a brief excerpt from the collection proves helpful:

I remember closely examining the opening in the head of my cock once, and how it reminded me of a goldfish's mouth.I remember goldfish tanks in dime stores. And nylon nets to catch them with.I remember ceramic castles. Mermaids. Japanese bridges. And round glass bowls of varying sizes.I remember big black goldfish, and little white paper cartons to carry them home in.I remember the rumor that Mae West keeps her youthful appearance by washing her face in male cum.I remember wondering if female cum is call “cum” too.I remember wondering about the shit (?) (ugh) fucking up the butt.I remember Ping-pong ball dents. (125-126)

First, the different associative leaps between “I remember...” statements bears mentioning. The relationship between the first and second sentences is both linguistic and figurative. “The opening in the head of [Brainard's] cock” reminds him “of a goldfish's mouth,” which leads him to a memory of “goldfish tanks in dime stores.” Comparing the meatus of the urethra to the mouth of a goldfish creates a comparative link within the initial statment; but the vehicle of the metaphor, which is the fish's mouth, reminds him of a dime store fish tank containing hundreds of literal goldfish mouths and, thus, produces the second statement. This memory, then, results in two more memories and a new type of association: a list of materially-related items. Whether it's “ceramic castles...Japanese bridges” or a “big black goldfish,” the content of every memory cataloged in these sentences adheres to one another on the material level.

Conceptually, the relationship between the black goldfish memory and the Mae West memory is the most radical, at least to the extent that there appears to be little, if any, connection. One could make a threadbare argument that a relationship between the color “white” and “male cum” bridges the divide between sentences, but even so, the connection remains tenuous. The foundation of the next association works through juxtaposition, contrasting male and female cum; and the subsequent sentence about “fucking up the butt” relates to the previous two statements on the level of discourse (in this particular instance, sexuality). The final “I remember...” statement from the excerpt could be consider disjunctive, similar to the black goldfish-Mae West linkage. By altering the types of association throughout the collection (e.g. linguistic, figurative, material, disjunctive, contrasting, or discourse-related), then, Brainard keeps readers on their toes and always in a state of curiosity as to where his mind will next take them.

Conceptually, the relationship between the black goldfish memory and the Mae West memory is the most radical, at least to the extent that there appears to be little, if any, connection. One could make a threadbare argument that a relationship between the color “white” and “male cum” bridges the divide between sentences, but even so, the connection remains tenuous. The foundation of the next association works through juxtaposition, contrasting male and female cum; and the subsequent sentence about “fucking up the butt” relates to the previous two statements on the level of discourse (in this particular instance, sexuality). The final “I remember...” statement from the excerpt could be consider disjunctive, similar to the black goldfish-Mae West linkage. By altering the types of association throughout the collection (e.g. linguistic, figurative, material, disjunctive, contrasting, or discourse-related), then, Brainard keeps readers on their toes and always in a state of curiosity as to where his mind will next take them.

The content of the above excerpt, as well, is indicative of the collection as a whole. To begin with, Brainard explores his (primarily but not exclusively homo)sexuality in explicit detail, never shying away from graphic or embarrassing subject matter. Whether he's hiding his semen-stained pajamas in the laundry from his mother, or getting a hand job from a stranger at the MoMA, nothing is off limits for his reportage. Pop culture is another preoccupation for Brainard, particularly movie stars, as evidenced with the invocation of Mae West. Whether it's Rock Hudson, Rosemary Clooney, Lana Turner, or Judy Garland, the poet's fascination with twentieth-century celebrities constantly reoccurs. Finally, the majority of the “I remember...” statements focus on memories from Brainard's childhood. And although the author's preoccupations are not exclusively from his earliest years (e.g. games, pranks, and day dreams, etc.), he does seem to find pleasure in tracing the circuitous paths of his more distant remembrances.

No comments:

Post a Comment