In a 2011 interview on Book Slut, Andrea Rexilius mentions that the conceptual genesis of Half of What They Carried Flew Away (Letter Machine Editions, 2012) stemmed from, in part, essays she taught in a composition class “on ways in which marginalized voices speak up to interrupt, or just to enter, and comment on or critique or call out or make visible a perspective previously shut out or unheard within the cultural narrative.” Not surprisingly, then, the tropes of boundary, crossings, and transformation employed by Rexilius echo those found within Gloria Anzaldua's Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, a foundational text for marginalized voices in the twentieth century.

Joan Pinkvoss, in her introduction to the third edition of Anzaldua's book, describes Borderlands/La Frontera as an “inclusive, many-voiced” (i) text that highlights identities “caught between los intersticios, the spaces between the different worlds” (iii). Similarly, in Half of What They Carried Flew Away, we find:

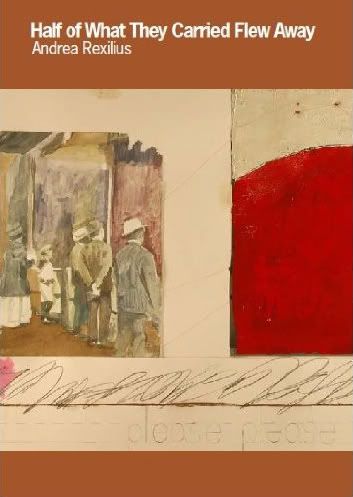

The most evident instance of a shaman aesthetic within Half Of What They Carried Flew Away occurs during one of the book's few image-laden passages:

Of course, there are differences between these texts. For example, Anzaldúa claims that the U.S.-Mexican border “es un herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third—a border culture” (25). Not only is this border inextricable from the body, but it is a body bleeding, scabbing, and bleeding once again. In contrast to Anzaldúa’s border as flesh, Rexilius writes:

Why, then, does the speaker of Rexilius's book promote material absence at a border? The answer, perhaps, can be found through a question Half of What They Carried asks of its readers: “What is the emanation of the image?” (23), where the image is a body inscribed. For the speaker of these poems, what emanates from the image is “contamination[,] a condition” (25) which produces “a cruel second nature” that places “limits” on one's “distinctions” (26). Accordingly, when a writer “decrease[s]...the images” within her writing, which for the most part Rexilius accomplishes, an “expansion” (49) results through abstraction. Abstraction, conceptualized in this manner, engenders a more protean and, thus, more egalitarian text that creates a fluid subjectivity. Subjectivity, as such, moves with less difficulty across borders, clearing a space for marginalized voices and a critique of dominant narratives.

Joan Pinkvoss, in her introduction to the third edition of Anzaldua's book, describes Borderlands/La Frontera as an “inclusive, many-voiced” (i) text that highlights identities “caught between los intersticios, the spaces between the different worlds” (iii). Similarly, in Half of What They Carried Flew Away, we find:

Furrows are created by circumstance. A type of fluid to recognize transformation. The above does not impose. Inner changes played out in outer terrains. Nothing happens to the image. These borders they live on, interrelated. (35)The confluence of “inner changes” and “outer terrains,” or the “border” on which they “interrelate,” comprise a zone of transformation wherein identity becomes “fluid.” Rexilius's collection concludes with:

I do not know what it is I am like.The speaker draws maps, escapes along lines of flight, is “neither a woman nor a man,” and admits that “I do not know what it is I am like.” To this extent, the non-gendered voice explores a mutable concept of self and participates in a “shaman aesthetic” wherein the storyteller transforms “into something or someone else” (Pinkvoss xviii); or, in Anzaldúa’s words, enters into “a place of contradictions” (19) located “at the juncture of cultures [and] languages” (20).

…

I am above all flight from flight.

I undertake not to represent, interpret or symbolize, but to make maps and draw lines

…

I am neither a woman nor a man in the light. (89)

The most evident instance of a shaman aesthetic within Half Of What They Carried Flew Away occurs during one of the book's few image-laden passages:

They needed a language to communicate with themselves.The transformation of bone, bark, and feather into forehead; or the human body, replete with river water, growing gills: these physical alterations for the sake of “communication” signal an arrival at Anzaldúa’s “place of contradictions” where nature and culture, among others discourses, intersect.

They put bones, pieces of bark, feathers into a tape recorder.

The meaning of the word forehead came out.

They come to the open between each breath.

They breathe out, grow gills and a river pours out.

Storms dissolve in their saliva.

They look up at the vast terrain, They've crossed over. (84)

Of course, there are differences between these texts. For example, Anzaldúa claims that the U.S.-Mexican border “es un herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third—a border culture” (25). Not only is this border inextricable from the body, but it is a body bleeding, scabbing, and bleeding once again. In contrast to Anzaldúa’s border as flesh, Rexilius writes:

A sea they say an origin.The confluence of elements, the border between land and water, is a “Bilingual place” just as Anzaldúa posits la frontera to be; but Rexilius's location is “Bodiless.” The speaker reinforces the absence of a body later in the collection, when she writes: “I have been told, it is unfair to say the word 'body' again. That's fine. It's easy enough to ignore” (35). One writer believes the body to be the epicenter, literally, of the new mestiza consciousness that must be “enacted” and “forever invoked” (89) in the flesh, whereas the other writer chooses to “ignore” the body.

I say sea, a place of incest. Holding something at bay.

Place where land and water meet. Bilingual place.

Place of water. Bodiless body. (21)

Why, then, does the speaker of Rexilius's book promote material absence at a border? The answer, perhaps, can be found through a question Half of What They Carried asks of its readers: “What is the emanation of the image?” (23), where the image is a body inscribed. For the speaker of these poems, what emanates from the image is “contamination[,] a condition” (25) which produces “a cruel second nature” that places “limits” on one's “distinctions” (26). Accordingly, when a writer “decrease[s]...the images” within her writing, which for the most part Rexilius accomplishes, an “expansion” (49) results through abstraction. Abstraction, conceptualized in this manner, engenders a more protean and, thus, more egalitarian text that creates a fluid subjectivity. Subjectivity, as such, moves with less difficulty across borders, clearing a space for marginalized voices and a critique of dominant narratives.

No comments:

Post a Comment