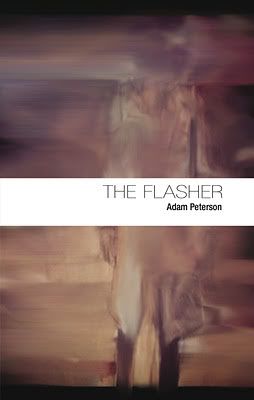

Adam Peterson's The Flasher (Springgun Press, 2012) is a series of sixty prose vignettes (and the occasional diagram) that documents the life of a character named “the flasher.” Given the title of the collection, as well as the protagonist's name, one would expect the book to detail the exhibitionist exploits of a man who exposes himself in public; but that is hardly the case. In fact, not until the final page of The Flasher does the flasher flash:

Intimately connecting with an other in a world in which we are “intractably alone” (8), then, is the overarching theme of Peterson's book. Throughout The Flasher, readers encounter scenes wherein connections are not made. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from “The flasher moves into a dollhouse”:

Desperate loneliness, though, is not a condition unique to the flasher; he's just one of the few to realize its pervasiveness. In “The flasher gives up the ghost,” Peterson presents us with a scene where “the girl and the ghost go off...skipping into the sunset hand-in-hand, not stopping to look into the other hand” (32) to know that it's empty.

Ultimately, the world of The Flasher is a world vacant of love, in which people say the words “I love you” only as “accidents” and “don't mean anything to the person saying them” (51). Yes, in this world, life is “a punishment considering [how] rarely” its inhabitants are “happy” (44). So foreign is the concept of love that, when the flasher tries to draw a heart, he can only muster a series of seemingly random symbols:

First, it's the belt of his trench coat dangling down to tickle his knee. Then it's his hat. After that, it's his sunglasses. The daylight blinds him. He can no longer see her, but she can see the whole of him. He counts to one instant then closes his coat, his eyes. His mouth is still open. And open. And open. (60)While this lone scene may be the “one instant” of premeditated, public exposure (once, the flasher accidentally exposes himself, and twice he is nude), it reveals to us the main character's desire to connect with another human being, literally opening himself to an other in hope of forming an intimate bond through undressing.

Intimately connecting with an other in a world in which we are “intractably alone” (8), then, is the overarching theme of Peterson's book. Throughout The Flasher, readers encounter scenes wherein connections are not made. Take, for instance, the following excerpt from “The flasher moves into a dollhouse”:

He tries to explain what has gone wrong to the blonde girl sitting next to him, but she cannot be bothered. No one is hungry. No one says welcome home. (10)Yes, scenes like the above occur often in The Flasher and present us with a portrait of a man who “sings [his] song alone” (17). While the flasher attempts to form a relationship with the girl who works at the muffin store throughout the course of the collection, the two never develop a meaningful rapport. In fact, the only person who appears to understand the flasher, at least somewhat, is his mother:

He chooses Julius. Because even though he's never wanted to be a Julius, he's always wanted to be someone who was once Julius but became Frank. But Frank doesn't work either, so he's Billy and Ernie and Debra before he settles on Clyde, but she keeps calling him the same thing when she hands him his muffin. He hasn't told her, he hasn't told anyone. Somehow his mother knows. She calls to say, O, Clyde, how did we grow so far apart? (14)Regardless of how many times the flasher changes his name, his mother still knows what to call him; but even she acknowledges that they have grown “so far apart.” When she finally succumbs to “sky cancer” (42), his world becomes “grey and cold and confused” (12) and lonely: a place from which he has “disappeared years ago” (24).

Desperate loneliness, though, is not a condition unique to the flasher; he's just one of the few to realize its pervasiveness. In “The flasher gives up the ghost,” Peterson presents us with a scene where “the girl and the ghost go off...skipping into the sunset hand-in-hand, not stopping to look into the other hand” (32) to know that it's empty.

Ultimately, the world of The Flasher is a world vacant of love, in which people say the words “I love you” only as “accidents” and “don't mean anything to the person saying them” (51). Yes, in this world, life is “a punishment considering [how] rarely” its inhabitants are “happy” (44). So foreign is the concept of love that, when the flasher tries to draw a heart, he can only muster a series of seemingly random symbols:

●How, then, should the flasher live his life; how, then, should we live our lives in a world crushingly devoid of understanding, intimacy, and love? The answer, it would seem, is to remain “open. And open. And open” in hope that one day we can foster a connection with someone else and share our most naked, exposed, and vulnerable instants.

©

Ö

Φ

◦ (58)

No comments:

Post a Comment