In one of the more famous statements by a poet on the relationship between poetry and grammar, Gertrude Stein wrote: “Do you always have the same kind of feeling in relation to the sounds as the words come out of you or do you not. All this has so much to do with grammar and with poetry.” Stein, notorious for non-normative grammar in her poetry, developed a unique relationship between herself, the sounds, and words she created when writing verse. In the final section of Lectures in America, she writes of those relationships at great length. Indeed, such an expansive investigation is evidence that, at least for Stein, when “you...learn grammar grammar is very exciting.”

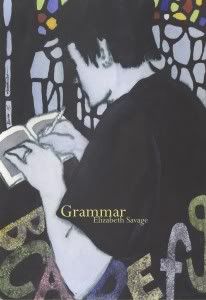

Reading through Elizabeth Savage's first full-length collection Grammar (Furniture Press Books, 2012), one quickly realizes that she too finds the rules of language construction very exciting, as she explores all that “has so much to do with grammar and with poetry appears.”

The book contains fifty-two poems, most of which bear titles corresponding to an element of grammar, such as “Misplaced Modifier,” “The Future Perfect,” and “Double Negatives.” Readers get an understanding of the importance the relationship between grammar and poetry holds for Savage in the poem “Grammar”; she writes:

The book contains fifty-two poems, most of which bear titles corresponding to an element of grammar, such as “Misplaced Modifier,” “The Future Perfect,” and “Double Negatives.” Readers get an understanding of the importance the relationship between grammar and poetry holds for Savage in the poem “Grammar”; she writes:

Drilled into instinctwe evolveby exceptionalitynoisy flockcontradictory art (39)

Certainly, primary school teachers figuratively drill grammar rules into their young students so they appear as “instinct” once they've grown accustomed to using language. In fact, many of those grammar drills that appear to be instinctive were actually poetry (or at least light verse) themselves. Who could forget the old rhyme “I before e except after c”? Of course, it's not so much a child's linguistic indoctrination that Savage champions. Instead, she claims that if we are to “evolve” as writers, poets, and artists, the old rules must be abandoned for word combinations infused with “exceptionality,” noise, and contradictions in order to produce an “art” that's complex, intriguing, and worthwhile. While Savage's poetry bears little aesthetic resemblance to Stein, both women comprehended the importance of non-normative usage.

The most compelling poems of Grammar are those that both play with the linguistic construct of their title and use language poetically. Take, for instance, the poem “Impersonal Pronouns (It, You, They)”:

They caught the criminalsresponsible for rainyou knew themby their bootsthe mastermind insiststhis—this—is bliss

Pointed out Imade my escape (47)

An impersonal pronoun, by definition, does not refer to a specific person, place, or thing. In the above poem, the pronouns “They” and “you” have no antecedents and, thus, cannot be attributed to a particular person. But over and above the engagement with grammar, there is much to admire. For example, the lines “They caught the criminals / responsible for rain / you knew them / by their boots” contains the absurd, dream-like imagery and humor of surrealism; while the poem's sonic elements, such as the alliteration in opening three lines or the overloaded slant-rhymes of the phrase “insists / this—this—is bliss,” push the poem forward with a well-crafted musicality. The poem concludes, then, with a double meaning that infuses the poem with sly wit: the “I” in the closing couplet can be interpreted as the inability of the pronoun “I” to express an impersonal form; or, having learned through the previous lines' examples what an impersonal pronoun is, the reader can now leave the poem and turn the page.

No comments:

Post a Comment