Joseph Cornell, an American artist from the mid-twentieth century, was best known for his shadow boxes; his glass-enclosed constructions contain assemblages collaged from

ephemera he found while on walking tours of New York City.

Adam Gopnik's article “Sparkings,” from a February 2003 issue of The New Yorker,

traces both Cornell's life as a man and his artistic influences. Of

Cornell's shadow boxes, he writes: they provide a “visual

experience of [a] city dweller,” in that the assorted bric-a-brac

arranged within them show “the joys of solitary wandering” from

Queens to Manhattan and back again. To Gopnik's mind, Cornell was a

window shopper par excellence, always scouring stores for a material object he could add to his own, miniature display cases.

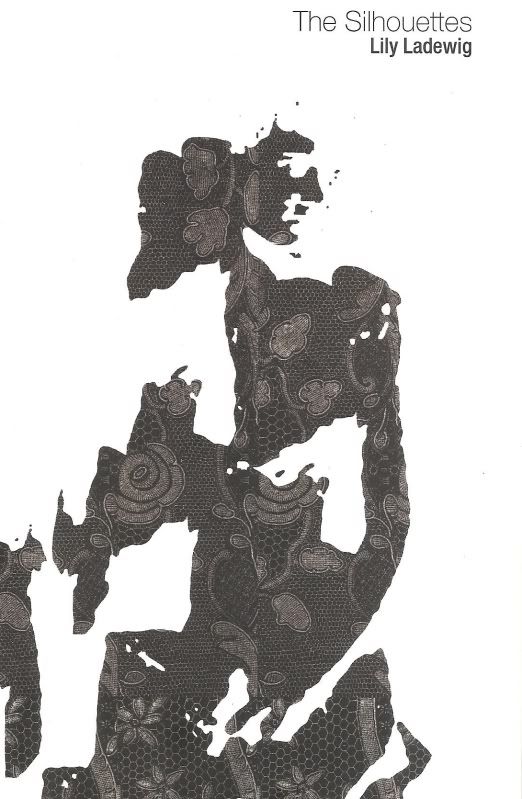

A

quick glance at the “Notes” section in the back matter of The

Silhouettes (Springgun

Press, 2012), which is Lily Ladewig's debut collection of poetry, reveals

her indebtedness to Cornell. The poet used several biographies, as

well as the artist's own notes and letters, as “inspiration and

source material” for the sequence of poems titled “Shadow Box”

that recurs intermittently throughout the collection. Take, for

instance, the first iteration of the series:

Let's build a fire. A shifting

location. A change of wind and I can smell myself. Like something

foreign. And into the fuller fascination. I can see the Chrysler

Building from the window of the subway car on the bridge. I would

measure the distance between us footwise. I would pull this poem from

you with my whole body. Beneath your bright palms my breasts might

become a reality. While my hands, full of acreage. Are budding

outside your open third story window. The dancers push their painted

feet across the page. (8)

Visually,

Ladewig shapes the poem into a square that mimics the form of

Cornell's shadow boxes and engages the material tradition of concrete

poetry. Syntactically, she writes in sentence fragments, their

piecemeal formation fostering an assemblage-like aura associated with

collage. But the content, as well, provides snippets of Cornell's

life and work: his New York City rambles in the image of “the Chrysler

Building from the window of the subway car on the bridge,” his

obsession with photographs of Hollywood starlets in the phrase

“Beneath your bright palms my breasts,” while “The dancers push

their painted feet across the page” acknowledges his preoccupation

with ballerinas and ballet.

Toward

the end of his New Yorker article,

Gopnik claims that Cornell's shadow boxes demonstrate:

The

balance of the metaphysical and the quotidian, the intimate address

and the popular symbols, the private mythologizing of mass culture,

the singing New York street and the oblique references, a dream of

France dotting the work like raisins in a pudding—all these things

are far closer to American modernist poetry than to its art.

While

it may be unfair to align or compare too closely The

Silhouettes with Cornell's

assemblages, the balancing act Gopnik addresses in the artist's work,

which he likens to “American modernist poetry,” can be seen in

Ladewig's verse. In the final set of “Shadow Box” poems, she

writes:

Repetition is necessary. It evens

out the body. I watch the Atlantic Ocean even out the evening.

Pressing silence into. Somewhere in the world you are moving and the

steps you take bring you closer to or farther from me. If only

slightly. What can I do with this room but remember it. I am getting

better. Something imaginary. I've been advised to hold my sadness in

my hands like a ball. To observe it. Something invisible. Fields of

poppies. Fields of wild. Lavender. In the Petit Trianon. Everyone

dressed in white. (62)

The

metaphysical does balance out the quotidian: the speaker, on the one

hand, says, “Repetition is necessary”; on the other hand, “I

watch the Atlantic Ocean.” Likewise, the Chrysler Building of the

earlier permutation balances itself against the “Petit Trianon”

of Versailles, juxtaposing New York City with France. More

than anything, though, The Silhouettes

achieves a balance between the universal and the specific by placing

epic images like “Sea foam green and the infinite numbers”

(44), next to the personal, such as a colloquialism like “I was so dunzo”

(45). In the end, Ladewig's “Small and glass-fronted” (45) shadow

boxes “function” as an “accumulation” (61): assemblages that

prove “The city is the place where” (30) we can collect ephemera

from our surroundings so as to build our most intimate

subjectivities.

No comments:

Post a Comment