At the

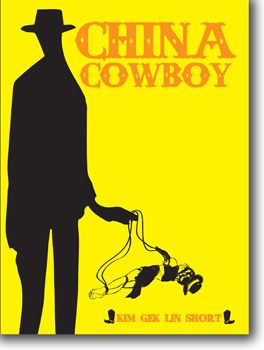

most rudimentary level, Kim Gek Lin Short's China Cowboy

(Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2012)

tells the story of a depraved relationship between La La and Ren, with Short building her nonlinear narrative through a series of

fragmented prose poems that alternate between the years 1989 and

1997. The story's premise focuses on Ren, an American from Missouri, who kidnaps La La, a twelve year old Chinese girl from Hong Kong, and

sexually assaults her over the course of eight years.

But

outside of the obvious themes of sexual abuse and criminal behavior,

China Cowboy offers an

interesting exploration of identity formation in an era of global

capitalism. In one of the first prose blocks, the collection's

narrator informs readers that “La La always wanted to be a cowgirl”

(5), a desire fueled by a childhood set to the soundtrack of American

country music:

La La liked to listen to music music all day she played her records.

Loretta Lynn Patsy Cline Emmylou Harris beautiful cowgirls. La La

never asked for anything but one day she asked for a guitar. Her

mother was hanging laundry out the kitchen window. Her mother blared

COWGIRLS DON'T HAVE FLAT FACES gave her daughter a clothespin. La La

put it on her nose. Wore it to school. Wore it to bed. Did not take

it off even dyeing her hair. (5)

La La idolizes

Lynn, Cline, and Harris, but her mother chides both this infatuation

and request for a guitar as ridiculous due to her “FLAT FACE.”

According to La La's mother, physical appearance dictates identity

and, therefore, is to a great extent immutable. Undaunted, La La

wears a closespin on her nose, risking pain and public humiliation in order to change her facial features and realize her dream of

becoming a American cowgirl singer.

But it's not just

her facial features that La La seeks to alter. The narrator also

mentions how, when she was “five or six,” La La sang “in her

corner of the bigger room practicing losing her accent” (49). It

would appear that her presistence pays off; in the prose poem “Fist

City,” the La La of 1997 has successfully transformed her vocal

patterns:

Y'all, where I come from there are no maps to it, and what y'all

don't know I trick it up. I had experience before I even met Ren, and

some of it weren't girls...Ya'll, I would've been out of your league

at 12. I'm only tattlin' now. (17)

Employing the

Southern-inflected “y'all” and “tattlin,” La La not only

loses her accent, but tailors her new voice to a particular region of the

United States in order to sound more like a cowgirl. Of course, by

erasing a past and replacing it with one that never existed, La La

must now admit that “where I come from there are no maps to it.”

Just because La La

can't map where she comes from, though, doesn't mean she can't

imagine an origin. While living in captivity, La La:

hears synthesized theme music from The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

and sometimes sees Clint Eastwood poncho-ed and posing in the

doorframe of the bathroom...From the look on Clint's face she know

they are thinking the same thing. She thinks, it is like they are the

same person. She thinks, it is like he is my blood father. (46)

In La La's

imagination, Clint Eastwood's character Blondie from the 1966

Spaghetti Western The Good, The Bad and The Ugly,literally,

becomes her biological father. On the one hand, the construction of

an originary tale based upon a movie starring an American celebrity,

no doubt, speaks to the all-consuming nature of American

entertainment and its hegemonic grip on global culture; on the other

hand, Sergio Leone, an Italian director, filmed the movie in Spain

primarily using European and Mexican actors. The American-self La La

constructs, in fact, is a transnational product from the beginning:

a European facsimile of an American Wild West that, itself, never

existed: imagination layered in imagination covering a forgotten

past.

La La, eventually,

questions the authenticity of Patsy Cline and the American life she

imagined. Before her kidnapping, she thinks:

When I get to America I will have my own room children in American

have their own rooms. It will have a lock on the door like when I'm

famous and have curled hair. When I get to America I can be anything

I can be Patsy Cline I have her wrists. (18)

After

Ren kidnaps her, though, her dream of a private room with a lock,

fame, and curled hair vanishes. La La can only wonder at “why the

white devil wants to hump so much” (13). First-hand experience

allows her to see through the smoke, mirrors, and movie sets of the

American Dream, revealing instead a “white devil” who “humps so

much” and leaves her covered in “semen loose warm stream dewlap

my hair saltwhite smeared” (28). In this depraved confusion, La La

turns to song in order to question how that dream and her imagined American identity managed to fail her: “Why

can't Batman play the guitar? / … / Why can't Elvis fly a

spaceship” (101)?

No comments:

Post a Comment