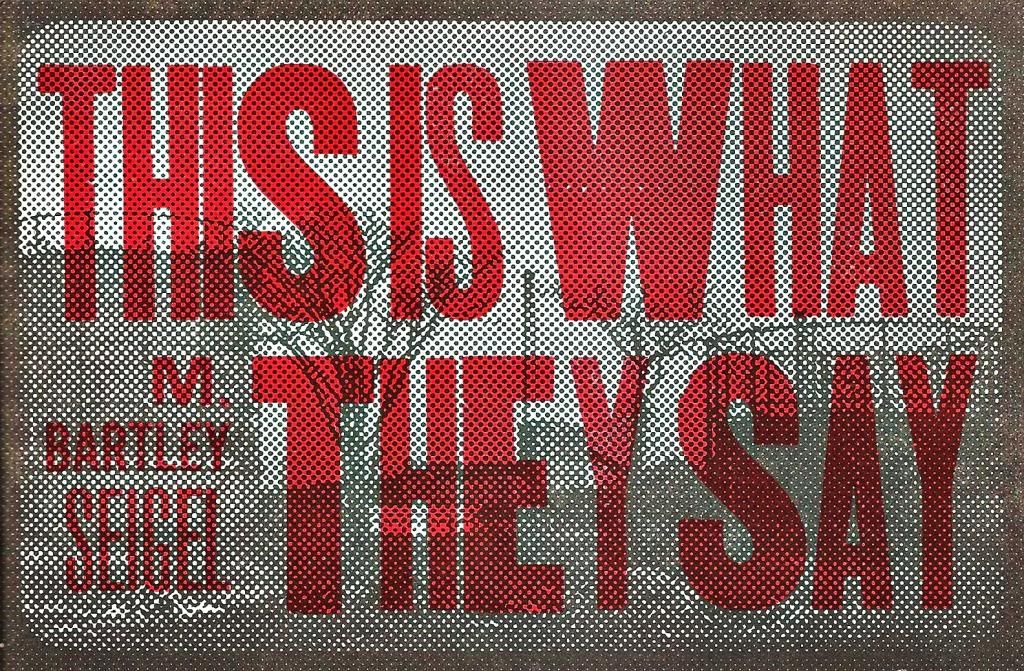

The dedication to M. Bartley Seigel’s debut collection This Is What They Say (Typecast Publishing, 2012) reads: “For the people and places in Montcalm County, Michigan, from a time when I called it home” (3). In many ways, the dedication speaks to the book’s primary concern: developing a poetics of place within a series of thematically linked prose poems.

Montcalm County is located in central Michigan, nestled between Grand Rapids and Saginaw, just northwest of Lansing. But a place is more than a location on a map; place is also an aura or feeling rooted in the land and the people who live there. As the introductory inscription to This Is What They Say states, Montcalm (and the book itself) is a “Strange country” filled with “ragged, roiling rage” (5); and this rage leaves imprints on the body:

In our basements we become aware that the scars on our knees aren’t those from third grade when we fell from the merry-go-round, something only our mothers will remember, but something darker, some emerging other self, hiding just beneath the surface. We see it in our eyes. (14)

Yes, this place engenders with its denizens “something darker” that hides “just beneath the surface” of the skin, scarring the body as it emerges. Later, the speaker of these prose poems says: “In this place we are all dead, pawing blind like a zombie through a junk drawer, searching among leaching batteries and rusted thumbtacks for a lost key” (27). As the dark self emerges, it transforms its host into walking death.

But This Is What They Say and the inhabitants of its terrain do not shirk responsibility for this transformation. They do not blame this darkness and death upon the land, some supernatural power, or an outside world that has forgotten them. Indeed, they know full well that they are complicit:

Terror embroidered; lock-jawed and dissembling, we are nightfall, thunderhead, mushroom cloud. Like a shockwave rippling across a darkening plain, our gravity is a dance, beautiful as a bullet. We bring down disaster no less than ever, always and never simultaneous, like a river beyond its banks, undeniable and insidious. (29)

The collective speakers of the poem, the “we,” are “nightfall, thunderhead, [and] mushroom,” portending, sounding, and actualizing the dangers of this “darkening plain.” Moreover, the speakers understand that they “bring down disaster” themselves, which is “undeniable and insidious.”

Of course, to reduce This Is What They Say to a dark catalog that festers up from underneath the Rust Belt’s surface would be a disingenuous. Midway through the collection, the speaker says: “They say not to speak of negatives, like the roof falling in, or the bottom dropping out, but we wonder what then to speak of” (36). Yet if we are not to speak badly of this place, how can we speak at all? Instead of conceding to an almost inevitable silence, though, the speaker takes the charge as a challenge, finding hope in a heretofore “unperceived existence” (36). He discovers “traces of laughter in the sky” (38), someone “imagine[s] places where we can breathe” (39), and intimate moments between lovers occur where “Kissing each other’s bodies, we cross our wires to test our hearts and heartbeats” (8), or “breathing in each other’s breath” in order not to “dislodge ourselves from each other, our sheets” (90). Yes, things might “fall apart easily and quickly” in this strange and ragged country; but if one looks close enough there are tender moments, albeit small and subdued.

The beauty of This Is What They Say, then, is the movement between tenderness and rage. As we traverse through the collection and observe the landscape around us, “our minds attentive to the contours of the land” (55), it is clear that:

Confusion and resentment might linger near the bottom of our cooked kettles, but something beautiful happened here once, something boiled steamed, and the scent of our tallow, our sweat and musk, will hang in the air for a while after we’ve gone. (57)

Indeed, there is confusion and resentment, but it’s mixed with something beautiful that hangs in the air long after we are gone and Seigel’s book is finished. And there can be no doubt we are better for having traveled through this complex country.

No comments:

Post a Comment