In 1978, Kip Tindell and Garrett Boone opened the first The Container Store in Dallas, Texas. According to the company’s website, the inaugural store offered customers:

commercial parts bins, wire drawers, mailboxes and popcorn tins, burger baskets, milk crates and wire leaf burners. The product collection was quite unusual, but when used in a home or office, the solutions would save customers space and, ultimately, time

Yes, The Container Store sold boxes and crates. Today, The Container Store sells “10,000 innovative products,” which is the company’s way of saying that it still sells boxes and crates, but now in different colors, shapes, and sizes.

The organizational properties of containers carries over into the layout of each Container Store, which designers have “divided into lifestyle sections marked with brightly colored banners such as Closet, Kitchen, Office and Laundry.” With mass-produced products sold in cookie-cutter stores located “from coast to coast,” anyone with a minimal amount of expendable income can place their household or work-related items in an overpriced storage unit that looks exactly like everyone else’s overpriced storage unit.

The organizational properties of containers carries over into the layout of each Container Store, which designers have “divided into lifestyle sections marked with brightly colored banners such as Closet, Kitchen, Office and Laundry.” With mass-produced products sold in cookie-cutter stores located “from coast to coast,” anyone with a minimal amount of expendable income can place their household or work-related items in an overpriced storage unit that looks exactly like everyone else’s overpriced storage unit.

Similarly named, the authors Joe Hall and Chad Hardy market their collaboratively written collection, The Container Store (Springgun Press, 2012), as a “product,” not a book. While the tag is certainly ironic, the collection is most appropriately labeled a conceptual poem that investigates the “poetics 0/ [of] space” in consumer culture and book design.

To begin with, Hall and Hardy write that “SPACE / should be an inclusive // stationary gulf,” but soon concede that now “Space is a product. [ ] / the clear plastic // panels keep everything / visible.” On the one hand, space should be an “inclusive gulf”: a universal abyss in which everyone can be surrounded or enveloped; on the other hand, companies such as The Container Store have transformed space into a “product” that holds our “everything” elses, which are also products. In other words, a physical and psychic dimension that once had the ability to induce deep thought or sublime sentiments has now been manufactured and sold to consumers as another base and unimaginative item.

Of course, it’s not only consumer culture that systematized and marketed space. Poets and publishers of poetry, generally speaking, accomplished the same task. Most books and journals today contain left-justified, lineated verse that uses standard fonts and enumerated pages. Obviously, there have been many exceptions to this rule over the years: William Blake’s Jerusalem, Susan Howe’s Thorow, Joshua Clover’s “Ça Ira” (and other concrete poems), and Edwin Torres’s The PoPedology of an Ambient Language just to name just a few. But the vast majority of published poems (today and otherwise) adhere to standardized spatial and visual conventions. Yes, poets and publishers churn out a lot of “AESTH / ETIC / PATTIES.”

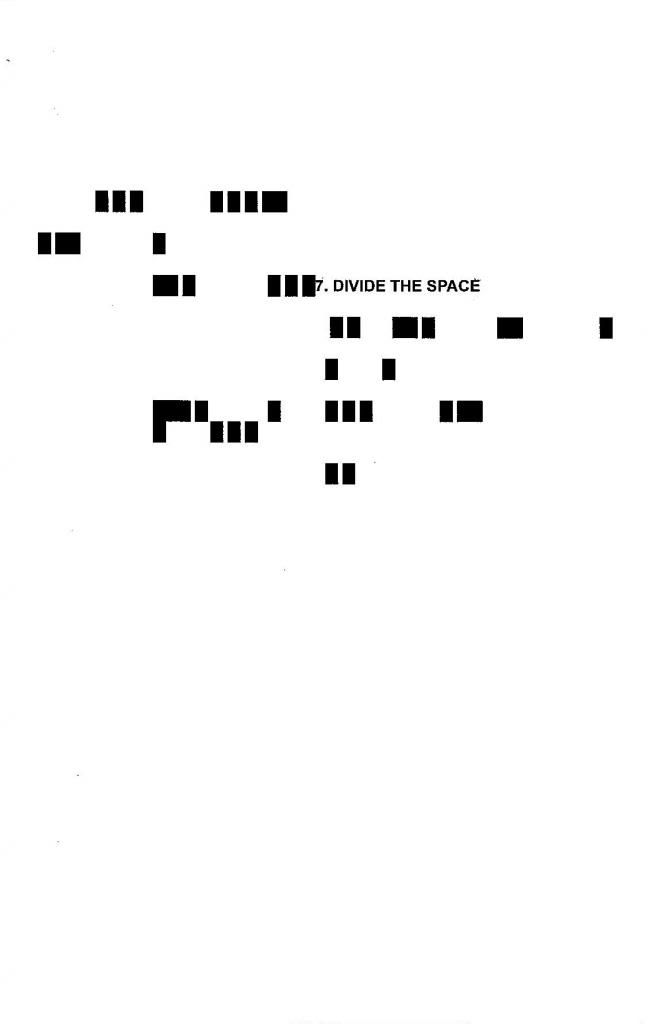

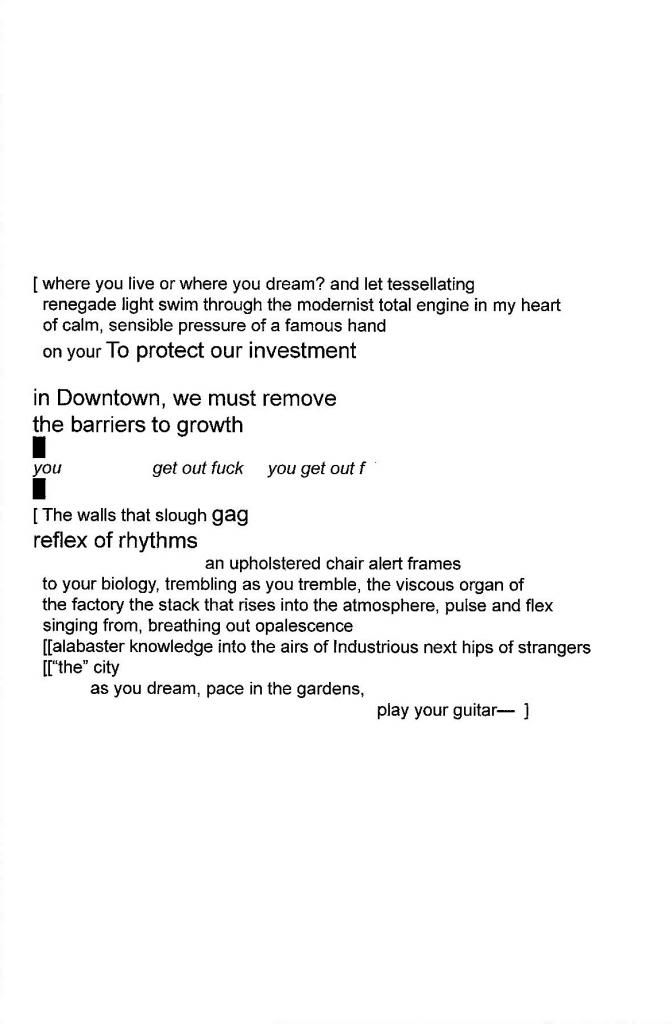

With these ideas, no doubt, in mind, Hall, Hardy, and the Springgun editors/designers created a conceptual poem that challenges these commonplace notions of space. Staggered alignments; multiple fonts, languages, and styles; an absence of pagination; the inclusion of non-linguistic signifiers; and exaggerated use of white space actively challenge the reader and require them to consider space as integral component of a poem. Moreover, they use space as a ground for play and experimentation. Take, for instance, the below screenshots (click on image for larger view):

All of these page images, in one way or another, use the entirety of the page as a spatial field that undermines conventional design and informs the text. And the words, or “the voice,” of these poems accomplishes the same task by “convert[ing] all space toexcess

|  |  |  |

All of these page images, in one way or another, use the entirety of the page as a spatial field that undermines conventional design and informs the text. And the words, or “the voice,” of these poems accomplishes the same task by “convert[ing] all space to

No comments:

Post a Comment