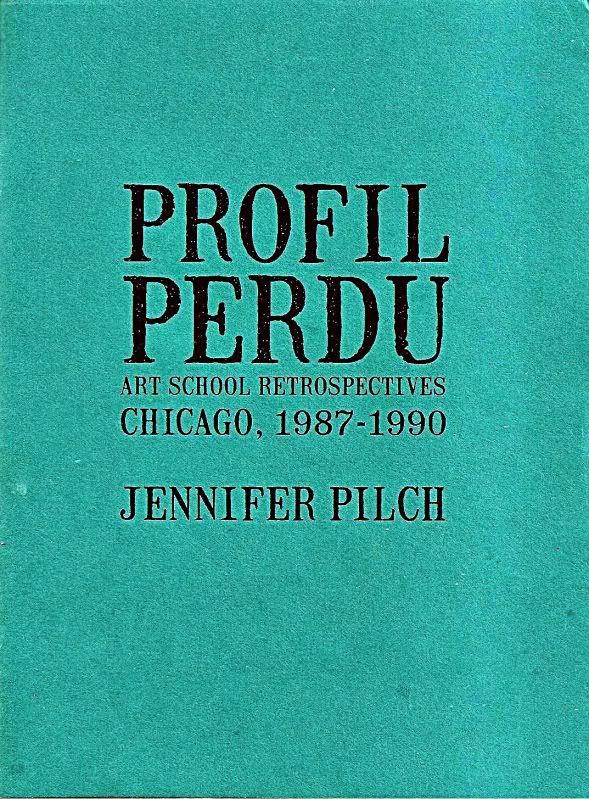

Jennifer Pilch's chapbook Profil Perdu, or “Lost Profile,” which is subtitled Art School Retrospective, Chicago, 1987 – 1990 (Greying Ghost Press, 2011), explores the inherent mysteries and difficulties associated with the process of producing art. In the opening lines of the collection, we find:

Far from the spectatorthe silhouette suggests movementIt frustratesthis act if turning awayStumps an intuition (3)

A “silhouette,” perhaps of the “spectator” herself, “suggests movement” at a distance. But whether the suggestion is actual movement or the appearance of movement, we cannot tell. The ambiguity of the unknown both “frustrates” the viewer and “Stumps [her] intuition."

If, in this case, a silhouette functions as a shadow painting or distorted representation of a real body, then it shares certain affinities with an art object. To explain, art objects tend to impede one-to-one correspondences between themselves and their real world counterparts because a movement, whether conceptual or representational, will always be suggested between the two. In other words, nothing is as it appears to be, including these so called “reflections.”

Certainly the poems within Profil Perdu are reflections, but they are also a “series of agitations” (7), in the sense that

If, in this case, a silhouette functions as a shadow painting or distorted representation of a real body, then it shares certain affinities with an art object. To explain, art objects tend to impede one-to-one correspondences between themselves and their real world counterparts because a movement, whether conceptual or representational, will always be suggested between the two. In other words, nothing is as it appears to be, including these so called “reflections.”

Certainly the poems within Profil Perdu are reflections, but they are also a “series of agitations” (7), in the sense that

once the view secured another aspectto conquer, glances melded—these fits—minnow stew (7)

Yes, an anxiety or agitation develops within the reader of the poem because once a particular “view,” reading, or understanding of the text is “secured[,] another aspect” or reading appears, which itself must be “conquered” or comprehended. Once an audience member secures that comprehension, the different readings must be “melded” together in an effort to form some composite knowledge of the text; but the aspects continue to multiply, necessitating additional melding, and further “fits” or agitations.

In addition to reflections and agitations, these poems are also “a trail of punctured translations” (17), in the sense that poems are thoughts transformed into words, which always leaves an irreducible space or “puncture” between them. But the punctured translation more often than not clears a space for beauty, as in the following poem:

Waking shakeneach groove felt between bricksomething coating the exigenta body of negative lightpearled edgesA bird flewI didn't noticeI was drawing them from ideathick strokes resembling wood cutsblack on white blinds flickering (10)

While one cannot be entirely certain of what occurs in the above poem, we know something poetic happens in the “Waking shaken” moments where dreams and reality merge and create “a body of negative light”: a being illuminated with darkness. Likewise, a bird flies by the speaker of the poem unnoticed, but she still manages to draw the bird “from [an] idea.”

The logic of these poems need not be questioned, for logic within a poem or an art object is not of primary concern. In fact, Pilch writes:

Difficult to plant oneself in a preconceived aestheticOne should rather wait to be supplantedby an emotion keen to geometryof trace clouds moving through a jigsaw (5)

Indeed, the source of the poem, of any art, does not derive from over thinking, planning, or designing (i.e. “a preconceived aesthetic”); instead, the speaker of the poem believes the poet or artist should “be supplanted // by an emotion.” And not just any emotion, but one that is atmospheric and ephemeral, yet also as precise as the “geometry / of trace clouds.”

This, of course, is not as easy as it sounds. In fact, the moment of entering a particular emotional geometry necessary for the production of art can be painfully difficult:

Cruel about losing trains of thoughtemotional knots to work their way outEmptier passages the closer one getsto keep (10)

Access to the emotional geometry necessary to write a poem can be “cruel” in that once someone touches upon a relevant concept, the train of thought that took them their can easily be lost. Likewise, once one attains the essential “emotional knots,” they can quickly “work their way out” and leave us with an empty “passage” and a failed attempt at poetry. But if one harnesses the necessary emotional geometry, poet, artist, and audience alike can revel in the beauty of creation.

No comments:

Post a Comment