One could easily mistake “Mommy V,”

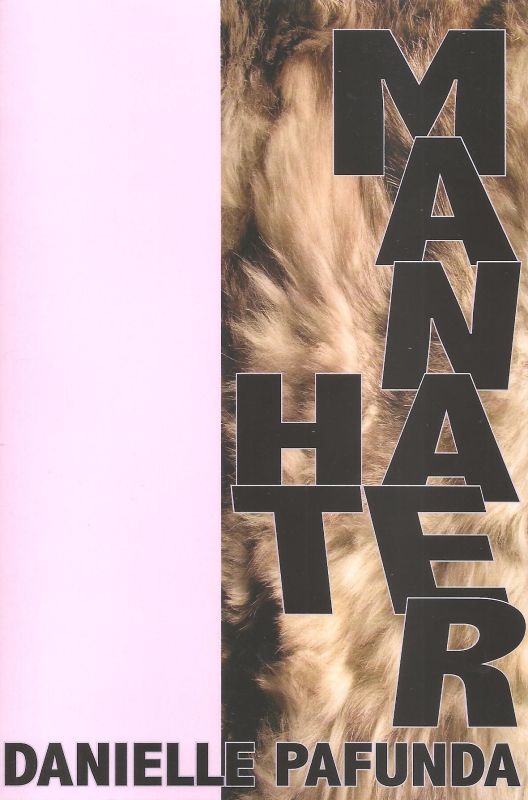

the 17-page sequence that opens Danielle Pafunda's Manhater (Dusie Press Books, 2012), as an off-shoot of the pop culture vampire-craze fueled

by the Twilight series

and its Buffy the Vampire Slayer

fore-bearers. The fact that the Mommy character “opens just wide

enough / to start the black wings rattling” (15) while “looking

for a likely bleed, a gush suck” (12) certainly does engage this

contemporary phenomenon. But “YA hotlings” (12) and those who

place too much stock in these cultural touchstones might miss a more

direct connection: Sylvia Plath's poem “Daddy,” which concludes

with the stanzas:

If

I've killed one man, I've killed two–

The

vampire who said he was you

And

drank my blood for a year,

Seven

years, if you want to know.

Daddy,

you can lie back now.

There's

a stake in your fat black heart

And

the villagers never liked you.

They

are dancing and stamping on you.

They

always knew it was you.

Daddy,

daddy, you bastard, I'm through.

The

speaker of Plath's poem kills her vampire father with a stake to his

“fat black heart” because he “drank [her] blood for... / Seven

years.” Pafunda, in turn, re-imagines Plath's speaker, also a

vampire, as an adult on the verge of motherhood. In many ways, the narrative of Manhater speaks to Donna Haraway's concept of cyborg writing, wherein writers

seize “the tools to mark the world that marked them as other. The

tools are often stories, retold stories, versions that reverse and

displace the hierarchical dualisms of naturalized identities.”

Plath's

daughter can only berate and chastise the memory of her deceased father.

By writing a sequel to “Daddy,” though, Pafunda provides the

daughter-now-mother with a more corporeal agency in her relations with men. And

how does the updated story of a blood sucking mother-to-be alter

those relations? “Mommy V” does this, mostly, by having the

protagonist cruise a “barren fuckscape” on a fabulous death-sex romp. Take, for instance, the following passage:

In

the park, she meets a man

who

smells like the trunk of a beater.

Mommy

gives him a sure thing.

She

gives him her favorite disease.

And

death. (16)

Soon

thereafter, Mommy meets another unsuspecting gentleman:

The

flaneur stud shakes toward her.

Off

the path for a piss, too cool

and

fatted about the skull.

When

Mommy's full, she's bored. (17)

Of

course, satiating her snuff-based libido isn't all its cracked up to

be. In fact, “Mommy hates sex, but she likes to orgasm” (21). The

desire for sexual pleasure, it appears, outweighs her disdain for the

act of sexual intercourse; but, perhaps, the killing of her sexual

partners mitigates the tension of these conflicting drives.

The

subsequent sections of Manhater

function, to some extent, as sequels and spin-offs of “Mommy V,”

examining more thoroughly grotesque, corporeal imagery. The “In

This Plate My Illness...” series explores Mommy's “favorite

disease” and the treatments she undergoes. For example, in one poem

Pafunda writes:

It

was a traumadome

and

a mummy cage.

I

hooked electrodes to the linen.

These

frothed and burned me

and

I became beautiful.

But

far too soon thereafter

fat

with suet, my seams split.

Out

seeped all the jolly worms

I'd

been hoarding. (33)

Pafunda offers image after image of a body deformed and damaged,

“frothed and burned,” split open and seeping “jolly worms.”

But in these grotesque images, the female body becomes “beautiful”;

at least to the extent that the poet, through her poems, creates and

champions a non-normative body and an idea of beauty on her own terms. Pafunda, very literally, takes Haraway's concept of story-tools, whether “electrodes,” a “vice of knives,” or a

“fucked instrument” (32), and marks the female body in order to

reform both it and the world.

“The

Desire Spectrum Is Dead To Me Now,” which concludes the collection,

combines elements of the first two sections over the course of a

sprawling, 21-page poem. It begins with a similar invocation of

tool-based imagery:

Which

of these do you want in you mouth?

Petroleum

hack cake, wire hanger,

rusted

piston, or silicone stopgap?

This

is a stick-up, an insomnia drill. (43)

Then

proceeds to moments of violent sexual relations:

Here

is the lover: carved like a mantis.

If

you limb him, they won't stop you.

Here

is the lover: a mouthful of nettles,

bleached

as a baby crab. (44)

That

ultimately prove unfruitful:

I

can't have an orgasm

large

enough to solve my problems.

To

solve any problems. (46)

And, of course, Pafunda continues to offer the reader grotesque depictions of the body:

You

gave me a disease like lyme disease,

which

you put in my thigh with your straw.

You

corpse stunk and puked fashion.

You

stubbed whatever you could

into

whatever I had. (48)

While any label, movement, or school employed by critics

(or poet-critics) to classify poetry should be only accepted

tentatively and with a high degree of skepticism, Manhater

certainly fits the “gurlesque”

moniker, which Arielle Greenberg argues: complicates “the relationship between feminism and

femininity...own their sexuality, wear it proudly, are thoroughly

enmeshed in the visceral experiences of gender...highly

conversational, lush and campy, full of pop culture detritus, and

ultimately very powerful.” Because, yes, Pafunda's book does

complicate femininity, sexuality, and gender through a “lush and

campy” fuckscape saturated in “pop culture detritus” and

“penumbral scuzz” (61).

No comments:

Post a Comment